For centuries, the way we represent the world on maps has shaped our understanding of geography, politics, and culture. Traditional projections, like the widely used Mercator, have long been criticized for distorting the relative sizes of continents, reinforcing a Eurocentric worldview. But over time, innovative cartographers have sought to challenge these distortions with alternative projections that offer a more balanced and accurate view of our planet. Two such approaches—the Cahill–Keyes projection and the AuthaGraph map—stand out for their unique methods of minimizing distortion and improving spatial representation.

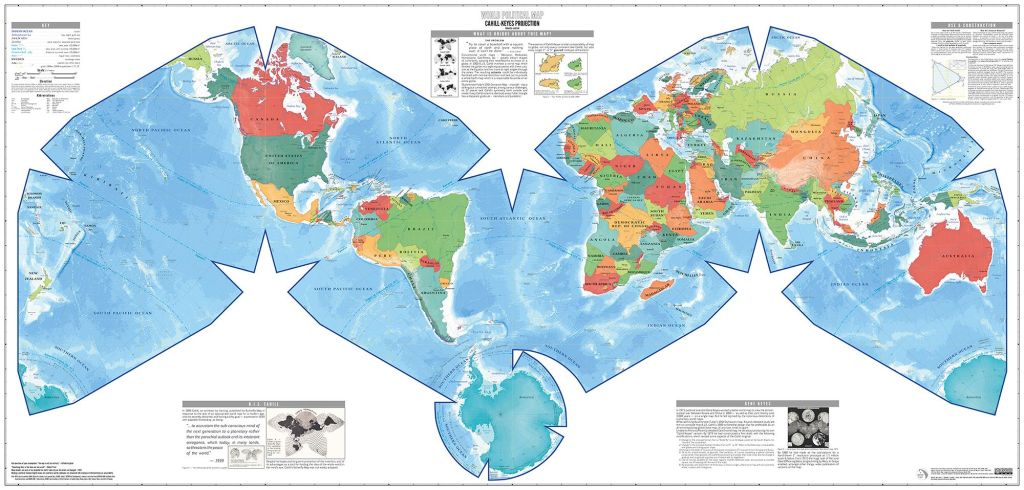

The Cahill–Keyes map, an evolution of Bernard Cahill’s 1909 “Butterfly Map,” was refined by Gene Keyes in 1975 to create a more symmetrical, contiguous world map. Unlike the Mercator projection, which greatly exaggerates landmasses near the poles, the Cahill–Keyes map unfolds the Earth into an octahedral shape, forming an “M” configuration that keeps continents connected while reducing distortion. By presenting landmasses with a higher degree of spatial accuracy, this projection fosters a more holistic view of global geography. It has been praised for its educational value, challenging the parochial perspectives often reinforced by traditional mapping systems.

The AuthaGraph map, developed in 1999 by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa, takes a different approach. Using a complex method of dividing the globe into 96 triangles and transforming it into a near-rectangular form, this projection maintains proportional relationships between continents and oceans better than most existing maps. The AuthaGraph gained significant recognition after winning Japan’s Good Design Grand Award in 2016, and has since been used in scientific and educational contexts to provide a more accurate representation of Earth’s geography. Unlike the Cahill–Keyes projection, which prioritizes contiguity, the AuthaGraph sacrifices some familiar visual continuity to achieve an exceptional balance of size and shape accuracy.

Both of these projections challenge outdated methods that have long influenced global perceptions. The Mercator map, despite its usefulness for navigation, has historically exaggerated the importance of northern regions while diminishing the size of Africa, South America, and other equatorial regions. These distortions have subtly reinforced geopolitical biases, making alternative projections like Cahill–Keyes and AuthaGraph essential tools for rethinking our worldview. While no single map can perfectly translate a three-dimensional Earth onto a two-dimensional surface, these newer projections push the boundaries of cartography, offering fresh perspectives that align more closely with reality.

Beyond their technical advantages, these maps serve a broader purpose in education and global awareness. The Cahill–Keyes map emphasizes planetary unity by maintaining continent contiguity, making it particularly useful for fostering a connected understanding of world geography. The AuthaGraph, with its emphasis on accurate proportions, is invaluable for scientific applications, such as climate modeling and oceanic studies. Both contribute to a growing movement that seeks to correct historical inaccuracies and promote a more equitable, data-driven representation of our planet.

In the end, cartography is as much about perspective as it is about accuracy. The Cahill–Keyes and AuthaGraph maps remind us that the way we visualize the world shapes the way we think about it. By embracing innovative projections, we take a step toward seeing Earth not just as a collection of distorted borders, but as a dynamic, interconnected whole.