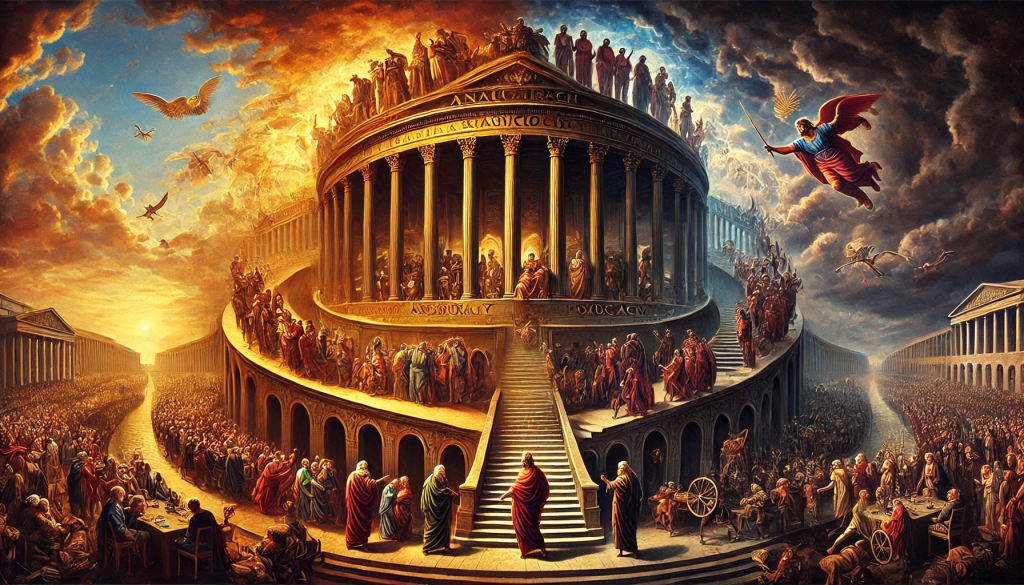

The United States was designed as a carefully balanced system, drawing from Polybius’ theory of anakyklosis, the ancient idea that governments cycle through different forms of rule as they degenerate. The Founders sought to prevent this cycle from repeating in America by creating a mixed government – a system that combined elements of monarchy (the presidency), aristocracy (the Senate and judiciary), and democracy (the House of Representatives and popular elections). This balance was supposed to be maintained through separation of powers and checks and balances, preventing any single branch from becoming dominant. However, over time, this system has eroded, leading to political dysfunction, growing authoritarian tendencies, and an increasing sense that American democracy is failing to sustain itself.

One of the most obvious signs of this breakdown is the expansion of executive power. The U.S. presidency, originally designed to be a limited office constrained by Congress, has grown into an institution that wields enormous influence over both domestic and foreign policy. Congress’ constitutional power to declare war has been effectively ignored for decades, with presidents engaging in military actions without formal approval. Executive orders, once meant for administrative matters, now serve as a way for presidents to bypass legislative gridlock and unilaterally shape national policy. Emergency powers, originally intended for genuine crises, have been used to consolidate authority, further tipping the balance away from Congress and toward the executive. What was once a system of monarchy constrained by law is increasingly resembling the early stages of tyranny, where power becomes concentrated in the hands of a single leader.

Meanwhile, the institutions meant to act as a wise, stabilizing force, the Senate and the judiciary, have themselves become distorted. The Senate, originally designed to serve as a check on populist excess, has become a bastion of partisan gridlock, where legislative action is often blocked not through debate and compromise but through procedural loopholes like the filibuster. The Supreme Court, meant to provide legal stability, has evolved into a de facto policymaking body, issuing rulings that shape national laws based on the ideological leanings of its justices rather than broad democratic consensus. The fact that justices serve lifetime appointments ensures that political biases from decades past continue shaping the present, often overriding the will of the electorate. Rather than serving as an aristocratic check on instability, the judiciary and Senate have increasingly acted as oligarchic strongholds, where entrenched power resists democratic accountability.

At the same time, the democratic elements of the system have begun to decay into their own worst tendencies. Gerrymandering has allowed political parties to carve up districts in ways that virtually guarantee electoral outcomes, stripping voters of meaningful representation. Populist rhetoric has taken over political campaigns, where leaders appeal not to reasoned debate but to emotional manipulation and fear-mongering. The rise of social media-driven outrage politics has further fueled division, turning every issue into an existential battle where compromise is seen as betrayal. The January 6th attack on the Capitol was not just an isolated event but a symptom of a deeper problem, the slide of democracy into oligarchy, or mob rule, where decisions are no longer made through structured governance but through force, intimidation, and the manipulation of public anger.

This erosion of balance has led to a state of chronic political paralysis. Congress, once the heart of American governance, now struggles to pass meaningful legislation, forcing presidents to govern through executive action. Public trust in institutions is collapsing, with many Americans believing that elections, courts, and government bodies are rigged against them. And looming over it all is the increasing potential for authoritarianism, as political leaders, on both the left and right, flirt with the idea that democratic norms can be bent, ignored, or rewritten to serve their interests. This is precisely the pattern that anakyklosis predicts: when democracy becomes too unstable, people turn to strong leaders who promise to restore order, often at the cost of their freedoms.

If the United States is to avoid falling deeper into this cycle, it must take deliberate action to restore the balance of power. Congress must reclaim its authority over war, legislation, and oversight. The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, may need reforms such as term limits to prevent long-term ideological entrenchment. Electoral integrity must be strengthened, ensuring fair representation through independent redistricting commissions and protections against voter suppression. And perhaps most importantly, the American public must become more politically literate, resisting the pull of demagoguery and demanding a return to governance based on reason, debate, and compromise.

Without these changes, the U.S. risks following the path of so many republics before it, where democracy fades, power consolidates, and the cycle of anakyklosis completes its turn once again.