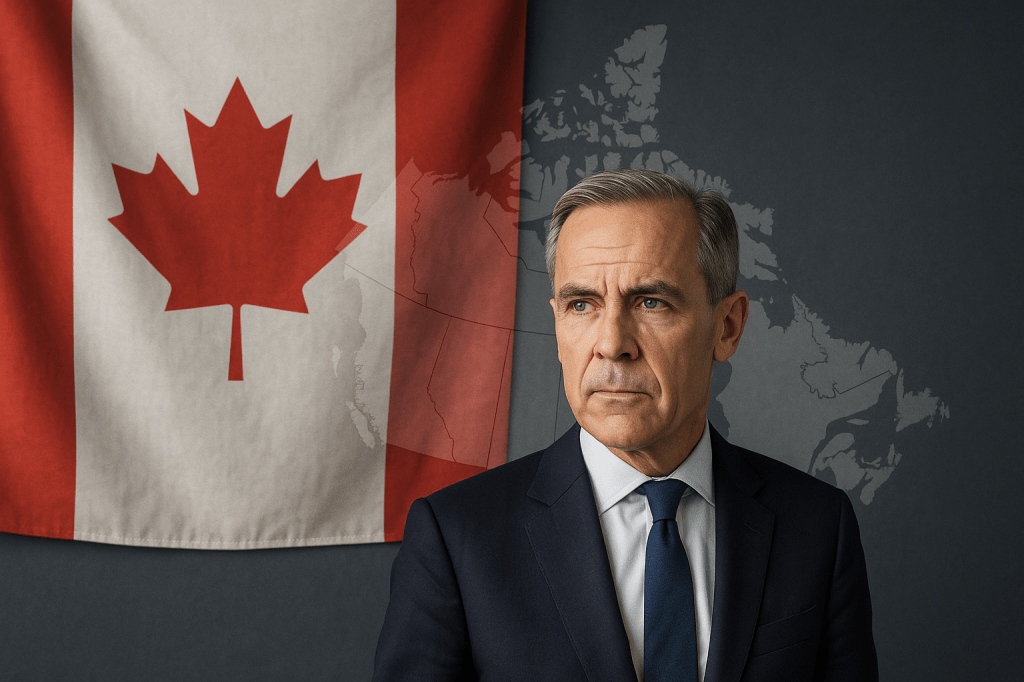

Mark Carney’s call for “one Canadian economy, not thirteen” isn’t just the idle musing of a former central banker with time on his hands, it’s the warning shot of a man who has sat at the helm of two of the world’s most powerful financial institutions and seen, up close, how countries succeed and fail. Carney’s frustration with Canada’s fragmented economic landscape is both practical and philosophical. He knows the potential this country holds – vast natural resources, educated people, global ties, but he also sees how much of it is squandered by a patchwork system where ten provinces and three territories act like neighbouring fiefdoms instead of building blocks of a common national purpose.

The problem, as Carney lays it out, is that Canada often behaves more like a loose confederation of mini-economies, than a modern unified state. Each region guards its turf: labour standards vary wildly, professional credentials don’t always carry across provincial lines, and tax regimes are a bureaucratic maze. Even something as basic as securities regulation, the rules that govern how companies raise money and protect investors, is balkanized, with no single national regulator, making Canada unique among developed nations in all the wrong ways. This isn’t just inefficiency; it’s economic self-sabotage.

Carney has always had a policy wonk’s precision, but in recent years he’s added the rhetorical flair of someone preparing to step onto the political stage. When he talks about the climate transition, for example, he doesn’t mince words: Canada will fail to meet its emissions targets if each province charts its own course. British Columbia might be ahead on carbon pricing, while Alberta and Saskatchewan cling to fossil fuels, and Quebec stands off in its own hydro-powered world. Without a shared strategy, Carney argues, we’re running thirteen separate races instead of pulling together in the global marathon toward sustainability.

Underlying Carney’s vision is a call for greater productivity and global competitiveness. He sees a Canada that could lead in clean energy, advanced manufacturing, digital innovation, but only if it acts in concert. That means building national infrastructure, fixing interprovincial trade barriers (which some federal estimates say cost the economy up to $130 billion a year), and aligning provincial policies on education, investment, and labour force development. It’s not just about growing the economy, it’s about making sure that growth is fair, inclusive, and forward-looking.

Of course, Carney knows the hurdles. This is Canada, after all. The constitution gives provinces enormous authority over key economic levers like natural resources and education. Regionalism runs deep, from the grievances of Western alienation to the distinct society of Quebec. Even the idea of a national strategy can provoke suspicion, seen less as vision and more as Ottawa’s overreach. And the political will to forge consensus is in short supply, especially in an age where short-term gains too often outweigh long-term planning.

Still, Carney keeps beating the drum. His is a voice urging Canada to get serious about itself. To stop coasting on inherited wealth and institutional stability, and start acting like a country that actually wants to lead in the 21st century. Whether as a private citizen, a public thinker, or elected Prime Minister, Carney is pushing us to imagine what Canada could become if it truly operated as one economy, not thirteen.

Sources:

Mark Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (Knopf Canada, 2021)

Government of Canada – Interprovincial Trade Barriers: https://www.canada.ca/en/intergovernmental-affairs/services/barriers-interprovincial-trade.html

Canadian Securities Administrators: https://www.securities-administrators.ca/