The United States stands today on the foundation of an unfinished revolution. The Civil War, often portrayed as the crucible in which the nation was made whole, was followed by a period of unparalleled opportunity to remake the republic. That window, known as Reconstruction, saw the brief emergence of a multiracial democracy in the former Confederate states, shepherded by the Radical Republicans in Congress. These were men who believed, fiercely and with moral clarity, that the war’s outcome demanded nothing less than the complete transformation of Southern society and the full inclusion of formerly enslaved people as citizens, voters, and landowners. What followed instead was a quiet, but definitive betrayal: a failure to complete the project of Reconstruction that left the white supremacist order largely intact, and gave rise to what some, including political commentator Allison Wiltz, now refer to as the “Second Republic.”

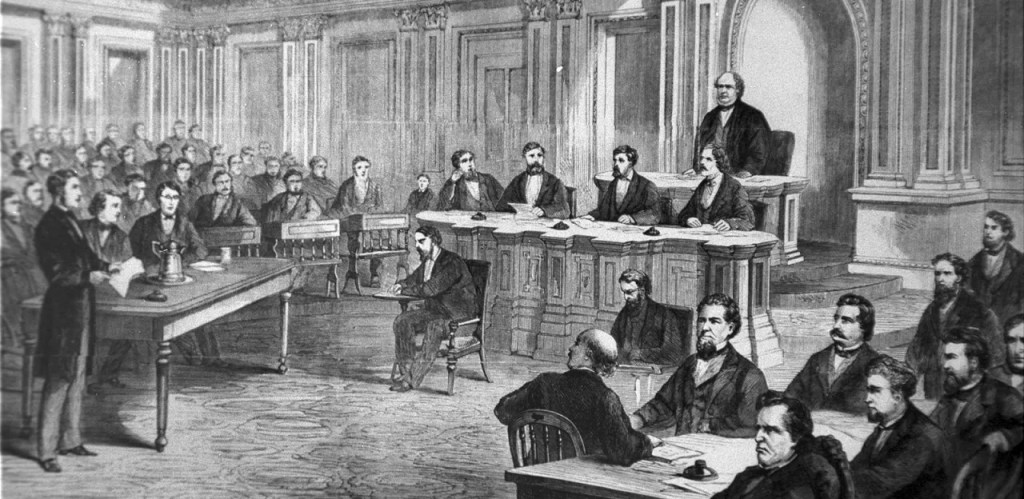

The Radical Republicans imagined a different America, one that would break the planter class’s hold over Southern life and reconstruct the country on the basis of racial equality and federal protection of civil rights. Their vision included land redistribution, the use of military force to protect Black communities, and the permanent disenfranchisement of Confederate leaders. The legal architecture was established: the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments promised freedom, citizenship, and suffrage. For a moment, this new republic seemed within reach. Black men voted and held office; schools and mutual aid societies flourished; and a vibrant, if fragile, political culture began to take root in the South.

Yet the resistance to this vision was swift and violent. Former Confederates, resentful and unrepentant, regrouped under new banners. Paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan emerged to intimidate Black voters and assassinate Black officeholders. Northern commitment to the cause of Reconstruction waned in the face of political fatigue, economic anxiety, and racist sentiment. The Compromise of 1877, which ended federal military occupation of the South, is widely recognized as the final nail in the coffin of Reconstruction. In exchange for a peaceful transfer of power in a contested presidential election, federal troops were withdrawn, effectively abandoning Black Southerners to white rule once again.

What emerged from this retreat was not the restoration of the antebellum order, but its mutation into something more insidious. The Southern elite reasserted dominance not through slavery, but through systems of racial control that would become known as Jim Crow. Sharecropping, vagrancy laws, and racial terror filled the vacuum left by federal inaction. In the North, corporate capitalism surged forward, aided by a Supreme Court increasingly hostile to civil rights and sympathetic to business interests. The new republic, this Second Republic, was forged not in the idealism of the Radical Republicans, but in the compromise between Northern capital and Southern white supremacy.

This betrayal continues to shape the American republic. The legacy of that failed Reconstruction is visible in the persistent racial wealth gap, in mass incarceration, and in the legal structures that continue to insulate white political power from meaningful multiracial challenge. It is felt in the enduring distortions of the Senate and Electoral College, institutions that grant disproportionate influence to states that once formed the Confederacy. It is also enshrined in the judicial philosophy that privileges state power over federal guarantees of equality, a doctrine born in the retreat from Reconstruction, and still central to American constitutional life.

What if the Radical Republicans had succeeded? That question, once the domain of counterfactual speculation, is now a central concern of a new generation of historians and public thinkers. They argue that the United States would have become a different nation entirely, one in which racial justice was not a belated corrective, but a foundational principle. A country in which democracy was not constrained by white fear and property rights, but energized by the full participation of all its citizens. In short, they argue that the real opportunity to found a just republic came not in 1776, but in the 1860s, and that the country blinked.

In this light, America’s long twentieth century: the civil rights movement, the New Deal, the struggle for voting rights, can be seen not as inevitable progress but as a series of rear-guard actions trying to recover ground lost in the 1870s. Each new wave of reform has faced the same obstacles that defeated Reconstruction: the intransigence of entrenched interests, the ambivalence of white moderates, and the enduring capacity of American institutions to absorb and deflect demands for justice. The Second Republic, born of compromise and fear, remains with us still.

To understand the full dimensions of America’s present crises, from voter suppression to white nationalist resurgence, requires reckoning with the moment the nation chose reconciliation over transformation. Reconstruction was not a tragic failure of policy; it was an abandoned revolution, and until that original promise is fulfilled, the United States remains a republic only partially realized, haunted by the ghosts of the one it refused to become.

Sources:

• Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877.Harper & Row, 1988.

• Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name. Anchor Books, 2008.

• Wiltz, Allison. “How the United States Became a Second Republic.” Medium, 2022.

• Du Bois, W.E.B. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880. Free Press, 1998 (original 1935).