There is a deceptively simple geographic fact that sits quietly beneath much of the current Arctic maneuvering. In the entire Arctic region, there is effectively only one deep-water port that remains reliably ice-free year-round without the benefit of icebreakers, and that port is Nuuk, Greenland. This is not a trivia point. It is a structural constraint that shapes strategy, logistics, and power projection across the high north.

Nuuk’s status is the product of oceanography rather than politics. The West Greenland Current carries relatively warm Atlantic water northward along Greenland’s western coast, keeping the approaches to Nuuk navigable even through winter. By contrast, most other Arctic ports, including those in northern Canada, are either seasonally accessible or require sustained icebreaking support. Russia is often cited as an exception, but ports like Murmansk rely heavily on infrastructure, icebreaker fleets, and state subsidy to maintain year-round access. Nuuk stands apart in that its ice-free condition is natural, persistent, and proximate to the North Atlantic.

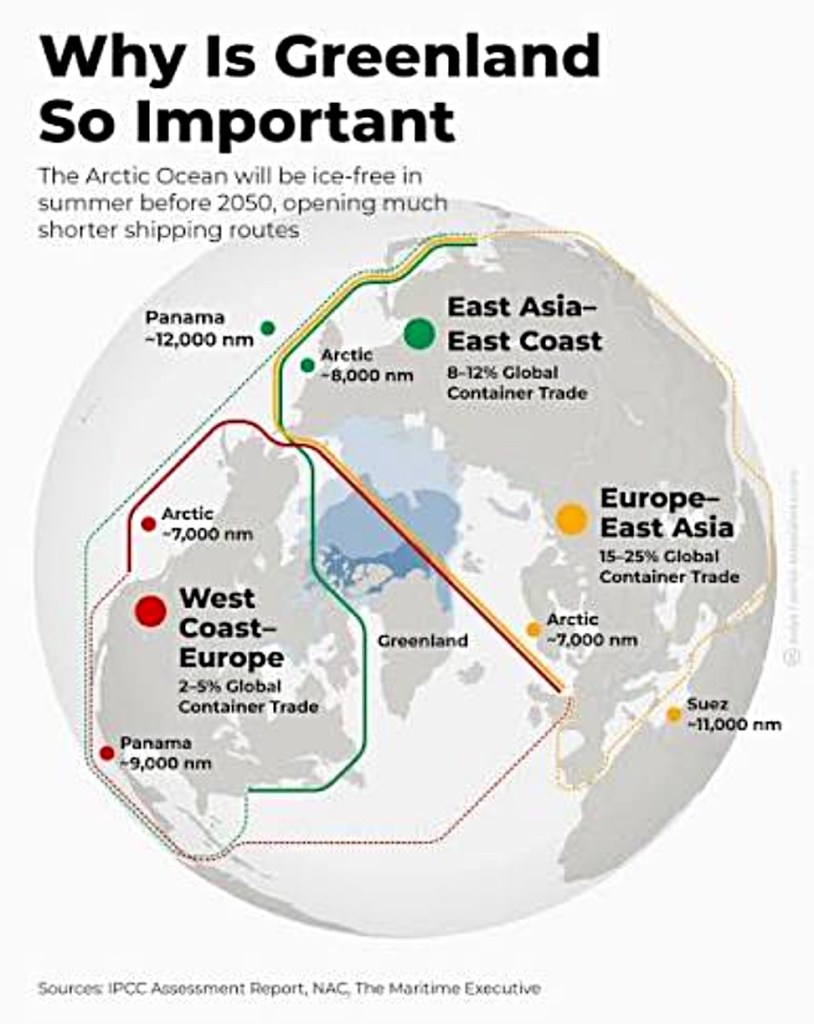

From a United States perspective, this matters enormously. American interest in Greenland is not primarily about territory in the nineteenth-century sense. It is about access, logistics, and denial. An ice-free port in the Arctic functions as a fixed node in what is otherwise a hostile operating environment. It enables sustained naval presence, resupply, maintenance, and potentially dual-use civilian and military shipping without the constant friction of ice conditions. In a future where Arctic sea lanes become more commercially viable and militarily contested, control or influence over such a node is strategically priceless.

This helps explain why U.S. engagement with Greenland has intensified well beyond rhetoric. Investments in airports, telecommunications, scientific infrastructure, and diplomatic presence all serve a dual purpose. They embed American interests into Greenland’s development trajectory while ensuring that any future expansion of Arctic activity occurs within a framework friendly to U.S. security priorities. The infamous proposal to “buy” Greenland was widely mocked, but it reflected a blunt articulation of a real strategic anxiety: the United States does not want its primary Arctic foothold to drift politically or economically toward rivals.

Canada’s position is more complex and, in some ways, more constrained. Canada has the longest Arctic coastline of any nation, yet no equivalent year-round ice-free deep-water port in its Arctic territory. This creates a persistent asymmetry. Canadian sovereignty claims rest on presence, governance, and stewardship rather than on continuous maritime access. The North is Canadian not because it is heavily used, but because it is administered, inhabited, and regulated.

As a result, Canada’s northern strategy cannot simply mirror that of the United States. Where Washington focuses on access and power projection, Ottawa must focus on resilience, legitimacy, and long-term habitation. Investments in northern communities, Indigenous governance, search and rescue, environmental monitoring, and seasonal port infrastructure are not secondary to sovereignty. They are sovereignty. Canada’s emphasis on the Northwest Passage as internal waters is inseparable from its need to demonstrate effective control without relying on year-round commercial shipping.

At the same time, the existence of Nuuk as the only naturally ice-free Arctic port creates both a vulnerability and an opportunity for Canada. The vulnerability lies in over-reliance on allied infrastructure. In any future crisis or competition scenario, Canadian Arctic operations would almost certainly depend on U.S. logistics routed through Greenland. The opportunity lies in cooperation. Joint development of northern capabilities, shared situational awareness, and integrated Arctic planning allow Canada to compensate for geographic disadvantages without surrendering policy autonomy.

What this ultimately reveals is that the Arctic is not opening evenly. It is opening selectively, along corridors dictated by currents, ice dynamics, and climate variability. Nuuk sits at the intersection of those forces. It is a reminder that geography still matters, even in an age of satellites and cyber power. For the United States, Greenland is a keystone. For Canada, it is a neighbor whose strategic weight must be acknowledged, managed, and integrated into a broader vision of a stable, governed, and genuinely Canadian North.

In that sense, the conversation about ice-free ports is not really about shipping. It is about who gets to shape the rules of the Arctic as it transitions from a frozen margin to a contested frontier.