Across a quiet stretch of rural Eastern Ontario, a storm is brewing, not of thunder and rain, but of land use, justice policy, and civic trust. In the town of Kemptville, just 60 kilometers south of Ottawa, the Ontario government has proposed building the Eastern Ontario Correctional Complex (EOCC), a 235-bed provincial jail, on what was once part of the Kemptville College campus; prime agricultural land with deep community roots.

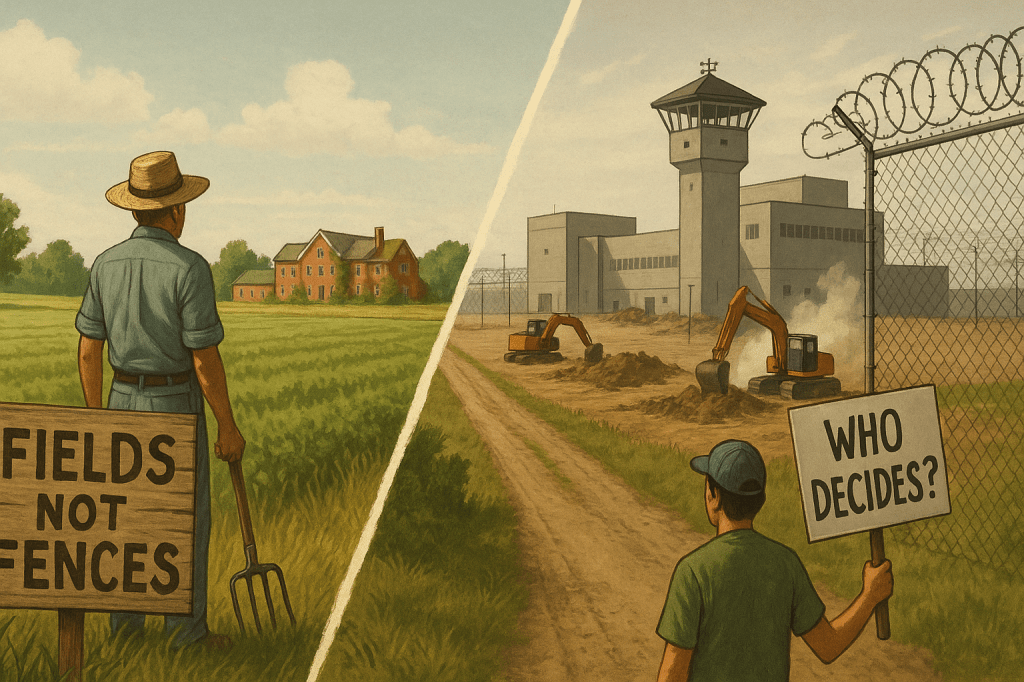

The story of this proposed prison is not only one of construction and policy, but of clashing visions for the future of Eastern Ontario. It is a story of farmland and fences, of children and correctional officers, of infrastructure gaps and political decisions. And perhaps most importantly, it is a story of a community asking why? Why here, and why now?

A Campus Reborn… and a Prison Across the Street

Following the closure of Kemptville College in 2016, the lands were acquired by the Municipality of North Grenville and repurposed into the Kemptville Campus Education and Community Centre. The site now houses educational institutions, youth programs, early learning centres, agricultural innovation hubs, and outdoor experiential learning, drawing hundreds of children and families onto the grounds daily.

Literally across the street, however, the province of Ontario plans to build a modern jail to alleviate overcrowding in Ottawa’s aged and strained Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre. In 2020, the EOCC was announced without prior consultation with local residents or municipal authorities. Since then, Ontario’s Ministry of the Solicitor General and Infrastructure Ontario have proceeded through environmental, geotechnical, and archaeological assessments, while the procurement process to select a construction partner continues.

In preparation, the province announced a $21.8 million investment in late 2024 to expand the local wastewater treatment facility, an infrastructure boost that would support both the prison and North Grenville’s projected population growth. While this has been framed as a win for the municipality, many in the community see it as paving the way for a facility they never asked for.

Local Voices, Deep Opposition

The backlash has been loud and sustained. The Coalition Against the Proposed Prison (CAPP) has been leading opposition efforts, supported by environmental groups, farmland advocates, and concerned citizens. Their concerns are rooted in what they see as a violation of planning principles: the conversion of 182 acres of prime farmland into a high-security facility in a region ill-equipped for such a purpose.

Their slogan – Fields Not Fences – captures the sentiment. To them, the decision is symbolic of a top-down, opaque approach to governance that neglects local values and long-term sustainability. And perhaps nowhere is this more palpable than on the Kemptville Campus itself.

What About the Kids?

With daycares, high schools, after-school programs, and even an agroforestry centre on the Kemptville Campus, many parents and educators are worried. While there are no official restrictions announced for youth-focused activities, the mere proximity of a medium-security correctional facility raises real questions.

Will the presence of the EOCC, even at a distance, impact perceptions of safety for school trips, outdoor learning, and daycare enrollment? Will families hesitate to send their children to programs just meters away from a working jail? These are not hypothetical concerns, they are being asked by parents, including Mayor Nancy Peckford, whose own children attend the Campus. In public statements, she has pushed the province for assurances, including appropriate setbacks and enhanced communication with the municipality.

The Ministry has agreed to locate the facility as close to Highway 416 as possible, rather than directly beside the campus. It has also committed to design considerations to shield the facility from view, but critics argue that no amount of landscaping can change the fact that children and correctional officers may soon be sharing a road.

Why Not Ottawa?

Perhaps the most confounding part of the province’s decision is its choice to build the jail outside of Ottawa. The provincial rationale, that Eastern Ontario needs more capacity, and that the Kemptville site is government-owned and available, seems less persuasive when weighed against logistical realities. Somehow it feels as if not having to purchase land in Ottawa was the main provincial concern.

Ottawa already hosts the region’s justice infrastructure: courts, legal aid offices, probation services, and public transit. Incarcerated individuals often require court appearances, mental health supports, and visits from family or counsel. Placing a prison in a small town without intercity transit creates additional barriers and isolates the incarcerated even further. It also forces staff to commute from Ottawa, increasing carbon emissions and reducing accessibility.

From an urban planning perspective, this is the antithesis of smart growth. It moves essential services away from existing infrastructure hubs, while forcing a rural community to absorb the impacts, social, environmental, and reputational, of a decision made elsewhere.

The Bigger Picture: Justice, Land, and Power

The Kemptville prison story reveals a broader tension between provincial power and local agency. On one side, a government seeking to modernize correctional infrastructure, reduce Ottawa’s jail overcrowding, and use its own land holdings efficiently. On the other, a community that sees farmland, education, and public trust being sacrificed for a carceral future they do not endorse.

It also reveals the contradictions in Ontario’s approach to land use and justice reform. While it invests in mental health, rehabilitation, and community supports rhetorically, its actions suggest a continued reliance on incarceration, disproportionately impacting Indigenous and racialised people. And while the province claims to value sustainable development, it is choosing to pave over productive farmland at a time when food security and climate resilience are becoming increasingly urgent.

What Comes Next?

Construction of the EOCC has not yet begun. The procurement process is ongoing, and opposition efforts, including a judicial review, are still active. What happens in the next year may determine not only the future of one community, but the direction of Ontario’s justice philosophy.

Will the province revisit its decision in light of sustained resistance? Will it reconsider siting the facility closer to Ottawa, where its infrastructure already exists? Or will it press forward, betting that time and investment will outlast protest?

For now, the fields across from Kemptville Campus remain untouched, but as bulldozers wait in the wings, the people of North Grenville are asking: are we building something we need, or destroying something central to a sustainable community?