The keel-laying of HMS Dreadnought in March 2025 marked a milestone in Britain’s strategic deterrent program and the future of its nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) fleet. As the first of four vessels in the new Dreadnought-class, this submarine embodies both an engineering triumph and a signal of sustained commitment to the UK’s Continuous At-Sea Deterrent (CASD), which has remained unbroken since 1969. At 153.6 meters and 17,200 tonnes, the Dreadnought will be the largest submarine ever operated by the Royal Navy: a floating cathedral of stealth, survivability, and silent lethality.

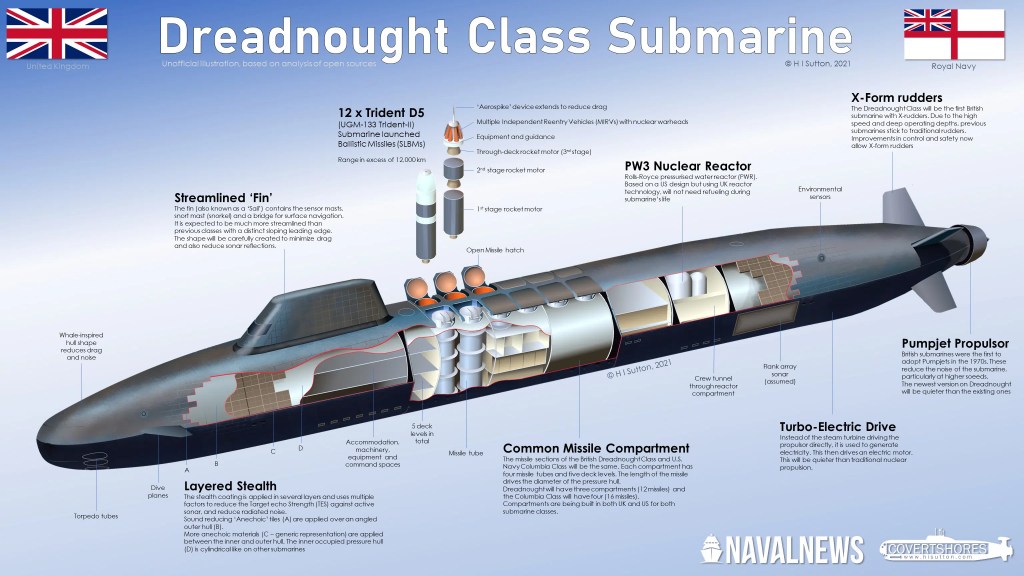

The new class is expected to replace the aging Vanguard-class submarines by the early 2030s and will be in service well into the 2070s. Powered by the Rolls-Royce PWR3 nuclear reactor, a substantial evolution from the PWR2 used in the Vanguards, the Dreadnoughts promise longer life, reduced maintenance, and quieter operation, essential for a vessel designed to avoid detection at all costs. Innovations in stealth include a reshaped hull form, advanced sound-dampening technologies, and X-shaped stern rudders for more agile maneuvering in deep water. The integration of BAE Systems’ Active Vehicle Control Management (AVCM) fly-by-wire system and Thales’ Sonar 2076 gives the submarine cutting-edge sensory and navigation capabilities.

Comfort and crew sustainability have not been overlooked. Designed to accommodate 130 personnel, the submarine includes improved living quarters, separate facilities for female sailors, a small gym, and an artificial lighting system to simulate day and night cycles, no small consideration for the psychological health of crews spending months submerged in strategic silence. Operationally, the class will carry 12 missile tubes using the Common Missile Compartment (CMC), co-developed with the United States. These tubes will launch the Trident II D5 ballistic missile, a weapon system that is central to the debate over British nuclear sovereignty.

For all its sovereign trappings, the UK’s nuclear deterrent is not entirely domestically independent. The Dreadnought-class, like its predecessor, remains intimately tied to US strategic infrastructure, a reality that undermines, in the view of some, the claim of an “independent” deterrent. The Trident II D5 missiles aboard Dreadnought are not built in Britain, but rather drawn from a shared pool maintained by the US Navy at Kings Bay, Georgia. These missiles are periodically rotated, serviced, and upgraded in the United States. The UK owns no domestic facility for full-cycle missile maintenance, which introduces a logistical and, some would argue, strategic dependency.

Even the warheads, while built and maintained at the Atomic Weapons Establishment in Aldermaston, are widely understood to be based on the American W76 design. British scientists have not tested a warhead since 1991, relying instead on simulation and US data. Further, the PWR3 reactor at the heart of the Dreadnought-class, although built by Rolls-Royce, is significantly influenced by the US Navy’s S9G reactor used in its Virginia-class attack submarines. This level of integration, from missile tubes to propulsion, reflects decades of close US-UK military cooperation, formalized in arrangements like the 1958 Mutual Defence Agreement.

Supporters of the Dreadnought program argue that such collaboration is not a weakness but a pragmatic alliance. By sharing R&D burdens and pooling procurement, the UK can field a credible nuclear deterrent without spending the tens of billions required for full-spectrum independence. Operational command and control of the submarines, including launch authority, remains fully in British hands, with final decision-making retained by the Prime Minister. Indeed, the “letters of last resort” carried on each submarine are uniquely British in character: a final instruction from one head of government to another in the event of national annihilation.

Yet critics maintain that the veneer of sovereignty cannot obscure the fact that a central pillar of British defence policy is structurally dependent on American goodwill, technology, and supply chains. In any future divergence of interests between London and Washington, or under a more isolationist US administration, the UK’s deterrent capability could be compromised, not technically, perhaps, but in terms of assuredness and resilience.

The Dreadnought-class represents both continuity and compromise. It is a technical marvel and a credible means of sustaining Britain’s strategic nuclear posture; but it is also a reminder that sovereignty in the nuclear age is often a layered illusion, one maintained not through autarky, but through alliance, collaboration, and trust in the enduring strength of an Anglo-American strategic partnership that remains, for now, as silent and watchful as the vessels patrolling the deep.