In Ontario, a quiet revolution in healthcare could begin with something as deceptively simple as a change in language. What if, instead of referring to the people they treat as patients, healthcare practitioners embraced the idea that they are working with clients? This shift in terminology is more than cosmetic; it signals a fundamental rethinking of how care is delivered and how relationships between practitioners and the people they serve are structured. Replacing patient with client disrupts the ingrained hierarchy of medicine, and opens the door to a model of care that is more collaborative, respectful, and, ultimately, more effective.

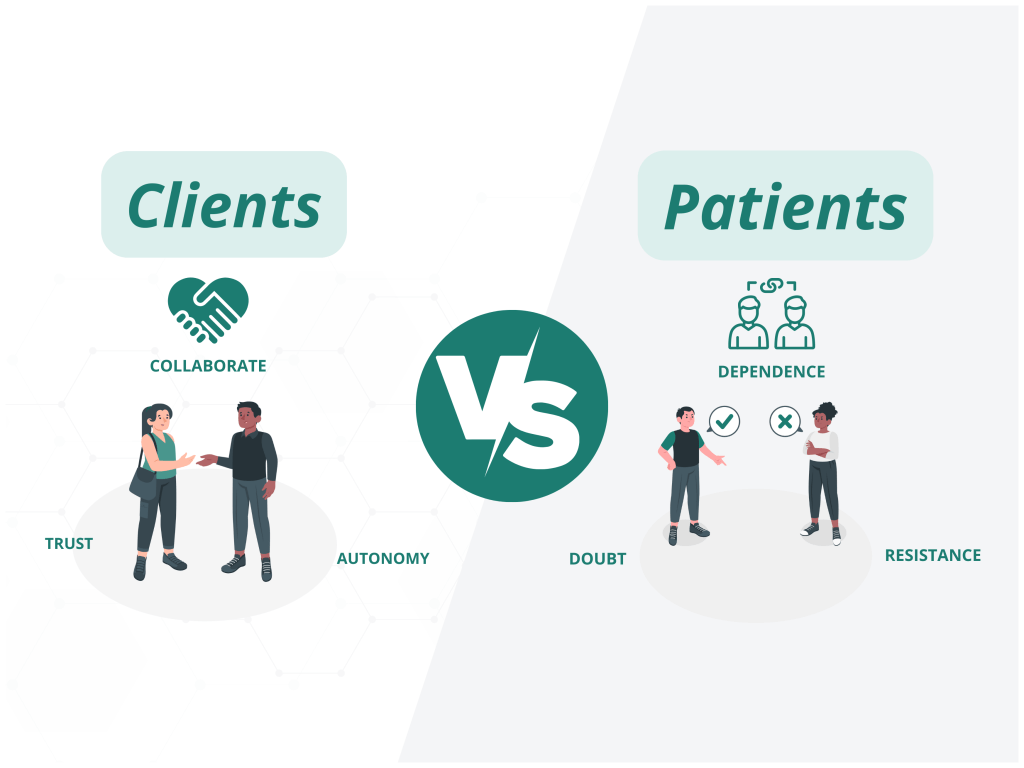

The word patient carries with it centuries of baggage. Rooted in a paternalistic tradition, it positions the healthcare professional as the authority and the person receiving care as a passive recipient. This model might be efficient in a short hospital stay or an emergency room visit, but it often falls short in the real world of chronic illness, mental health, elder care, and preventive services. In these domains, success relies less on technical intervention and more on sustained relationships, shared goals, and mutual trust. Reframing the care recipient as a client changes the dynamic entirely. A client has agency. A client has choices. A client is someone with whom you work, not someone you work on.

This idea is hardly radical in other professions. Lawyers, accountants, architects, and business consultants, all highly educated, tightly regulated professionals serve clients, not patients. These roles are steeped in trust and responsibility, yet they operate from a baseline assumption that the client is an informed actor. Professionals in these fields provide guidance, analysis, and expertise, but they do not presume to make personal decisions on behalf of the people they serve. If such a standard is good enough for legal or financial matters, why should health, arguably the most personal domain of all, be treated differently?

Adopting a client-centred lens has profound implications for healthcare delivery. It reshapes informed consent from a bureaucratic formality into a genuine process of dialogue and understanding. It places a premium on listening, cultural humility, and the social determinants of health. It encourages practitioners to see people not just as carriers of disease or disorder, but as whole individuals navigating complex lives. In Ontario’s increasingly diverse and pluralistic population, this shift is especially urgent. Language, history, trauma, race, and gender identity all influence how people experience healthcare. Treating them as clients creates space for those realities to be acknowledged and respected.

More importantly, research consistently shows that when people are treated as partners in their care, outcomes improve. Chronic disease management, medication adherence, mental health recovery, all benefit from a model in which individuals are active participants rather than passive recipients. Community Health Centres, Nurse Practitioner-Led Clinics, and Indigenous-led health organizations have long embraced this ethos, often with outstanding results. These models recognize that healthcare is not merely about procedures and prescriptions; it’s about relationships and empowerment.

To make this shift from patient to client more than a philosophical exercise, Ontario’s healthcare system must engage in a formal change management process that embeds this transformation into everyday practice. Change at this scale requires more than individual will, it demands structural alignment, leadership buy-in, and sustained cultural development. Medical and nursing schools must be at the forefront, redesigning curricula to emphasize collaborative care, cultural safety, and relational ethics from day one. Teaching hospitals and clinical settings must model this new language and ethos consistently, ensuring that learners observe and internalize client-centred care as the norm, not the exception. Professional colleges, health authorities, and policy-makers need to articulate a unified vision and provide concrete supports; from updated documentation protocols to ongoing professional development. Without a deliberate, system-wide strategy to guide this cultural transition, the risk is that well-meaning practitioners will continue operating in structures that reinforce the very hierarchy we seek to move beyond. True transformation will require education, reinforcement, and accountability across the health system.

Of course, this shift will not be easy. Medical training in Ontario still often reinforces an expert-knows-best mentality. Fee-for-service billing structures reward speed over depth, and systemic pressures, from staffing shortages to rigid bureaucracies, can make relational care feel like a luxury rather than a standard. Some professionals resist the term client, worrying it sounds too commercial or transactional. But in truth, it’s a term of respect. It conveys that the individual has power, and that the practitioner has a duty to serve, not command.

If Ontario is serious about building a more equitable, sustainable, and humane healthcare system, it must begin by reimagining the core relationship between practitioner and person. Words matter. They shape expectations, behaviours, and culture. Shifting from patients to clients could be the first step toward a system that doesn’t just deliver care, but shares it.