The Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) faced a significant defeat in the 2025 federal election, despite early leads in the polls. Several factors related to their platform and campaign strategy contributed to this outcome.

Ideological Ambiguity and Policy Reversals

Under Pierre Poilievre’s leadership, the CPC attempted to broaden its appeal by moderating positions on key issues. This included adopting a more serious stance on climate change and proposing policies aimed at working-class Canadians. However, these shifts led to confusion among voters about the party’s core principles. The rapid policy changes, especially during the short campaign period, made the party appear opportunistic and inconsistent.

Alienation of the Conservative Base

The CPC’s move towards the center alienated a portion of its traditional base. This disaffection contributed to the rise of the People’s Party of Canada (PPC), which saw its vote share increase significantly. Many former CPC supporters shifted to the PPC, attracted by its clear stance on issues like vaccine mandates and opposition to carbon taxes. This vote splitting weakened the CPC’s position in several ridings.

Controversial Associations and Rhetoric

Poilievre’s perceived alignment with hard-right elements and reluctance to distance himself from controversial figures, including former U.S. President Donald Trump, raised concerns among moderate voters. Trump’s antagonistic stance towards Canada, including economic threats and inflammatory rhetoric, made the election a referendum on Canadian sovereignty for many voters, pushing them towards the Liberals.

Ineffective Communication and Messaging

The CPC’s campaign suffered from inconsistent messaging. While initially focusing on pressing issues like housing, the campaign later shifted to a more negative tone, attacking Liberal policies without offering clear alternatives. This lack of a cohesive and positive message failed to inspire confidence among undecided voters.

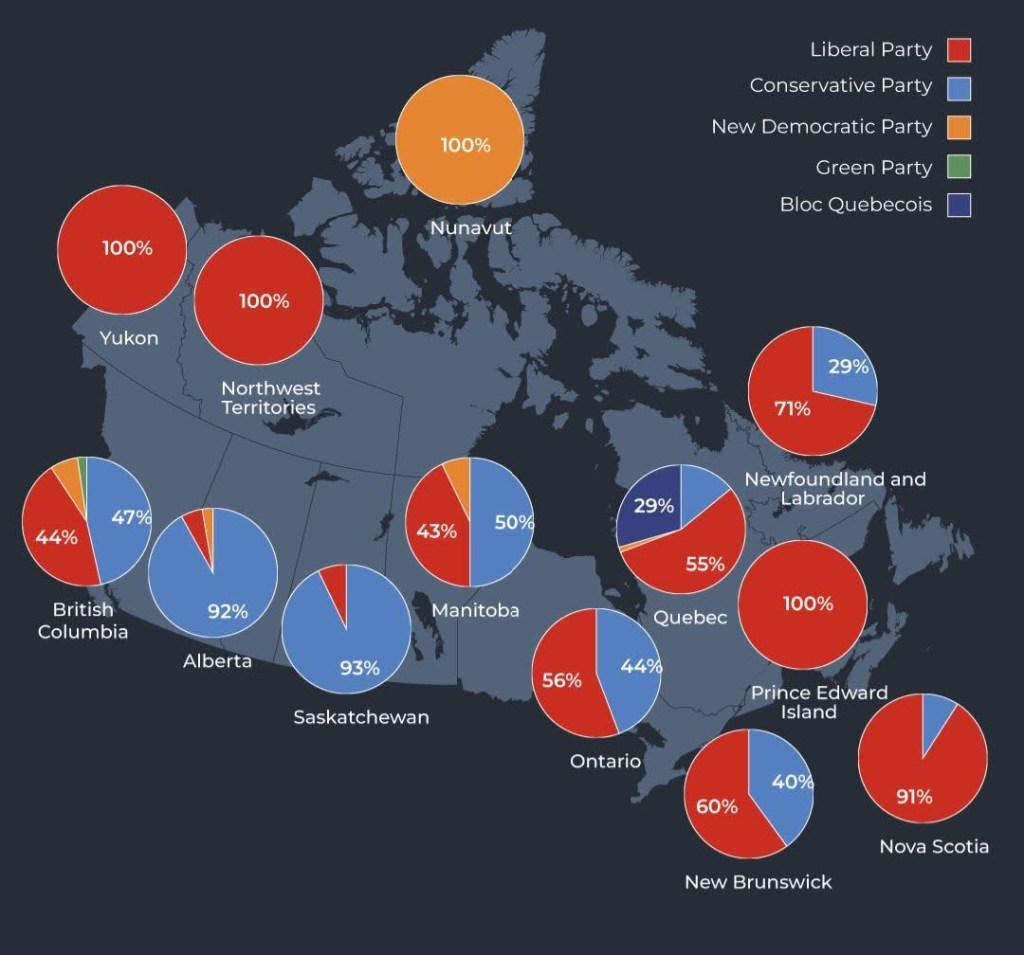

Structural and Demographic Challenges

The CPC continued to struggle with regional disparities, particularly between conservative-leaning western provinces and liberal-dominated urban centers in the east. The party’s inability to appeal to urban and suburban voters, coupled with changing demographics, hindered its ability to secure a national majority.

Foreign Interference Concerns

Post-election analyses indicated that foreign interference, particularly from Chinese government-linked entities, may have influenced the election outcome. Disinformation campaigns targeted CPC candidates, especially in ridings with significant Chinese-Canadian populations, potentially costing the party several seats.

The CPC’s defeat in the 2025 federal election can be attributed to a combination of ideological shifts that alienated core supporters, associations with controversial figures, inconsistent messaging, structural challenges, and external interference. These factors undermined the party’s ability to present a compelling and cohesive alternative to the electorate.