On Canada’s west coast, the phrase “the Big One” has drifted too easily into metaphor. It is used casually, invoked vaguely, and then set aside as a distant abstraction. The most recent British Columbia Disaster and Climate Risk and Resilience Assessment strips that comfort away. What it describes is not speculative catastrophe but a rigorously modelled scenario grounded in geology, history, and infrastructure analysis. A magnitude 9.0 megathrust earthquake off Vancouver Island is not only possible; it is among the more likely high-impact earthquake scenarios facing the province.

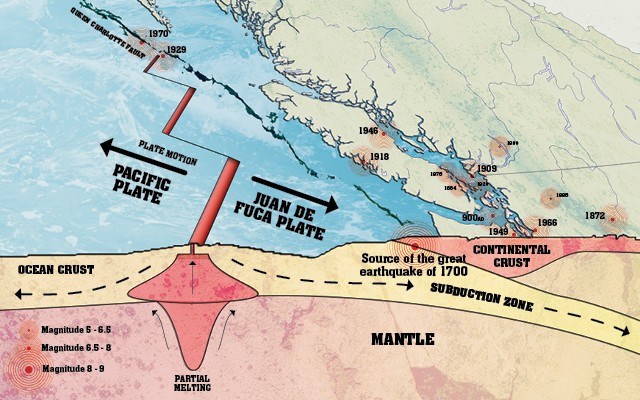

The source of the risk is the Cascadia Subduction Zone, where the Juan de Fuca Plate is slowly, but inexorably being driven beneath the North American Plate. This is not a fault that slips frequently and harmlessly. It locks, accumulates strain over centuries, and then fails catastrophically. The last full rupture occurred in January 1700, an event reconstructed through coastal subsidence records in North America and tsunami documentation preserved in Japanese archives. Geological evidence indicates that such megathrust earthquakes recur on timescales of hundreds, not thousands, of years. In emergency management terms, this places Cascadia squarely within the planning horizon.

The provincial assessment models a magnitude 9.0 earthquake occurring offshore of Vancouver Island. The projected consequences are stark. Approximately 3,400 fatalities and more than 10,000 injuries are expected. Economic losses are estimated at 128 billion dollars, driven by the destruction of roughly 18,000 buildings and severe damage to at least 10,000 more. These figures do not rely on worst-case fantasy. They emerge from known building inventories, population distribution, soil conditions, and transportation dependencies. They reflect what happens when prolonged, intense shaking intersects with modern urban density.

Geography shapes the damage unevenly, but decisively. Vancouver Island bears the brunt, particularly along its western coastline, where proximity to the rupture zone amplifies shaking and tsunami exposure. Eastern Vancouver Island, including Victoria, remains highly vulnerable due to soil conditions and aging infrastructure. On the mainland, a narrow, but densely populated band stretching from the United States border through Metro Vancouver to the Sunshine Coast experiences significant impacts, especially in areas built on deltaic and reclaimed land. Liquefaction in these zones undermines foundations, buckles roadways, and fractures buried utilities, compounding the initial damage long after the shaking stops.

The earthquake does not arrive alone. A tsunami follows as an inseparable companion hazard. The assessment projects wave arrival on the west coast of Vancouver Island within 10 to 20 minutes, leaving little time for anything other than immediate self-evacuation. The east coast of Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland face longer lead times, roughly 30 to 60 minutes, but also greater population exposure. In parallel, major aftershocks, widespread landslides, fires ignited by damaged gas and electrical systems, and flooding from compromised dikes and water infrastructure unfold across days and weeks.

Probability is often misunderstood in public discussion, oscillating between complacency and panic. The assessment estimates a 2 to 10 per cent chance of such an extreme event occurring within the next 30 years. That range may sound small, but emergency management does not measure risk by likelihood alone. It multiplies likelihood by consequence. A low-frequency, ultra-high-impact event demands attention precisely because recovery, once required, will dominate public policy, fiscal capacity, and social stability for decades.

Comparative modelling reinforces this conclusion. United States federal planning scenarios for Cascadia earthquakes project casualty figures in the tens of thousands when the full Pacific Northwest is considered. Insurance industry analyses warn that a major Cascadia rupture would strain or overwhelm existing insurance and reinsurance systems, prolonging recovery and shifting costs to governments and individuals. These are not contradictions of the British Columbia assessment but confirmations of its scale.

What emerges from this body of evidence is not a call for fear, but for seriousness. Preparedness for Cascadia is not primarily about individual survival kits, though those matter. It is about seismic retrofitting of critical infrastructure, realistic tsunami evacuation planning, protection of water and fuel lifelines, and governance systems capable of functioning under extreme disruption. It is also about public literacy: understanding that strong shaking may last several minutes, that evacuation must be immediate and on foot, and that official assistance will not be instantaneous.

The Big One is not an unknowable threat lurking beyond prediction. It is a known risk with defined parameters, measurable probabilities, and foreseeable consequences. The only variable that remains open is how well institutions and communities choose to prepare. History shows that Cascadia will rupture again. Policy choices made before that moment will determine whether the event becomes a national trauma measured in generations, or a severe but survivable test of resilience.

Sources:

British Columbia Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness. Disaster and Climate Risk and Resilience Assessment, October 2025, Chapter 5 Earthquake Scenarios. Province of British Columbia.

Yahoo News Canada. “B.C. report warns magnitude 9.0 quake could kill thousands.” 2025.

Geological Survey of Canada. Earthquakes and the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Natural Resources Canada.

U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake and Tsunami Planning Scenarios.

Wikipedia. “Cascadia Subduction Zone” and “1700 Cascadia Earthquake.”