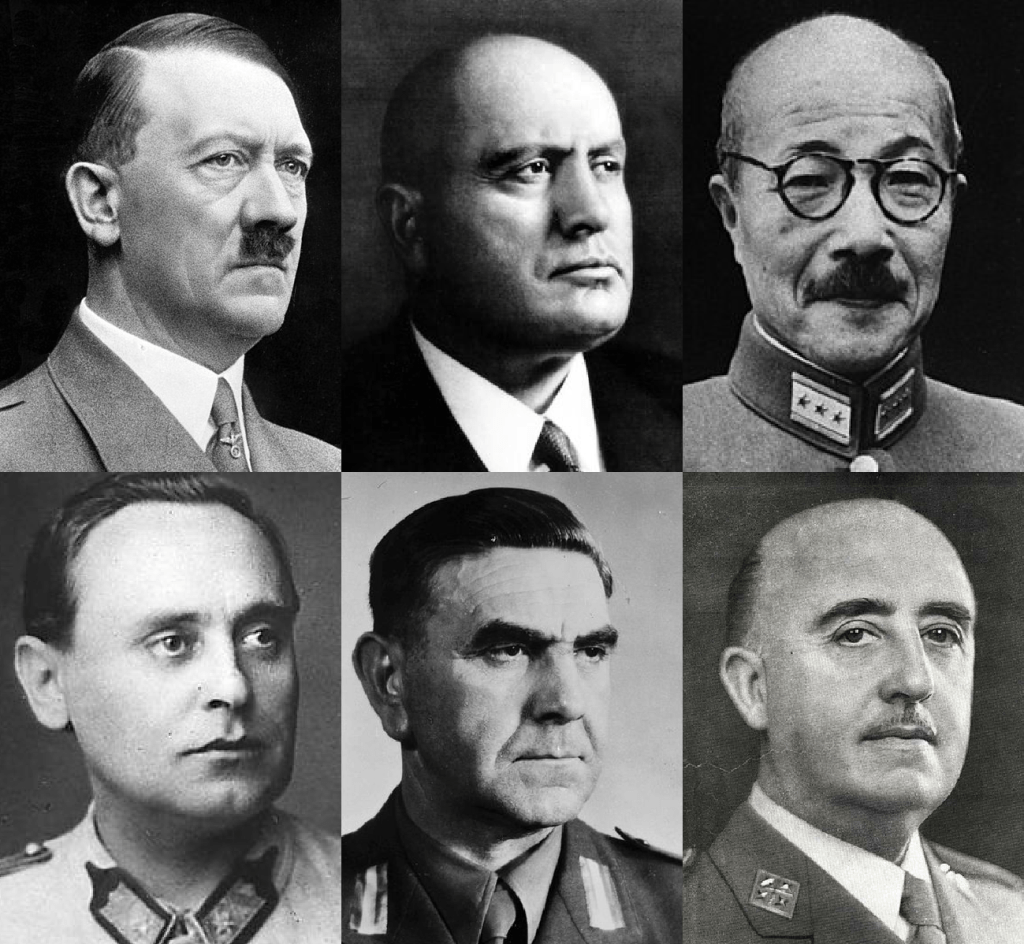

Fascist and authoritarian leaders rarely see themselves as doomed figures in history. On the contrary, they often believe they are exceptional – capable of bending the course of history to their will. Whether through the cult of personality, the rewriting of historical narratives, or sheer force, they assume they can control how they will be remembered. This delusion has led many to catastrophic ends, yet new generations of authoritarians seem undeterred, convinced that they will be the ones to succeed where others failed. Trump and his allies fit squarely into this pattern, refusing to believe that history might judge them harshly or that their actions could lead to their own downfall.

Mussolini provides one of the most vivid examples of this phenomenon. He envisioned himself as a modern-day Caesar, reviving the grandeur of the Roman Empire through Fascism. His brutal repression of dissent, his alliance with Hitler, and his reckless military ambitions ultimately led to disaster. When the tide of World War II turned, Mussolini found himself abandoned, hunted, and finally executed by his own people; his corpse hung upside down in Milan as a stark rejection of his once-grandiose vision. And yet, to the very end, he believed he was the victim of betrayal rather than the architect of his own demise.

Hitler, too, was utterly convinced of his historical greatness. He meticulously curated his own image, producing propaganda that cast him as Germany’s savior. Even as the Third Reich collapsed around him, he ranted in his bunker about how the German people had failed him rather than the other way around. His ultimate act, suicide rather than surrender, was an attempt to control his narrative, ensuring he would never be paraded as a prisoner. But history did not grant him the legacy he sought. Instead of being remembered as a visionary, he became the ultimate symbol of genocidal tyranny.

The pattern continued into the later 20th century. Nicolae Ceaușescu, the Romanian dictator, had convinced himself that his people adored him. He built extravagant palaces while his citizens starved, crushed opposition, and developed a personality cult that portrayed him as a paternal figure of national strength. When the moment of reckoning arrived in 1989, he seemed genuinely shocked that the crowd in Bucharest turned on him. Within days, he and his wife were tried and executed by firing squad, their supposed invincibility revealed as an illusion.

Even those who manage to hold onto power longer do not always escape history’s judgment. Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile through terror for nearly two decades, believing that his iron grip would secure him a revered place in history. But his crimes – torture, executions, forced disappearances eventually caught up with him. Though he escaped trial for most of his life, his reputation was destroyed. His legacy became one of shame rather than strength.

Trump, like these figures, operates in a world where loyalty and spectacle take precedence over reality. He dismisses mainstream historians as biased, preferring the adulation of his base over any broader judgment. He likely assumes that as long as he can retain power, whether through elections, legal battles, or intimidation, he can dictate how history views him. But history has a way of rendering its own verdict. Those who believe they can shape their own myth while trampling on democratic institutions, rule of law, and public trust often find themselves remembered not as saviors, but as cautionary tales.