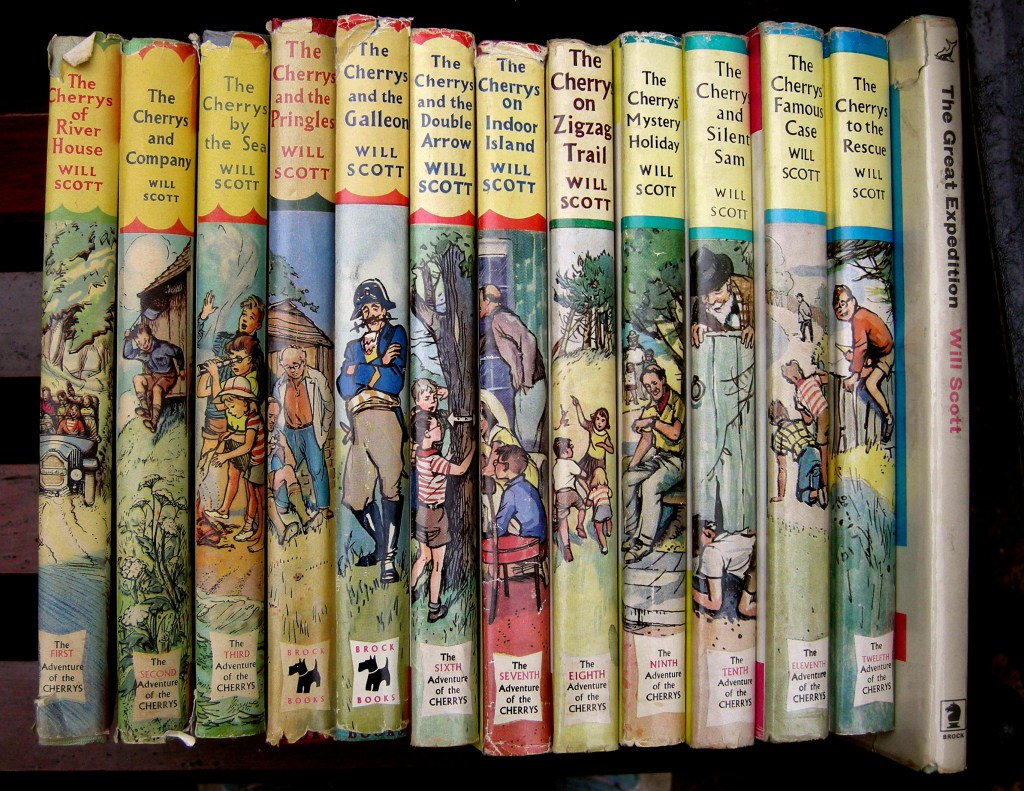

William Matthew Scott, better known by his pen name Will Scott, was a British writer born in 1893 in Leeds, Yorkshire, and active as a novelist, playwright, short-story writer, and children’s author until his death in 1964 in Herne Bay, Kent. In his earlier career he wrote detective novels and plays including The Limping Man, and is said to have contributed around 2,000 short stories to magazines and newspapers, which was considered a record in the United Kingdom during his lifetime. His shift into children’s fiction came relatively late and was inspired by his own grandchildren, for whom he began inventing stories that eventually became The Cherrys series.

Published between 1952 and 1965, The Cherrys consists of 14 books aimed at children around ten years old. These books are set in a series of fictional English villages and bays, often around the Kentish coast, and centre on a single extended family: Captain and Mrs Cherry and their four children, Jimmy, Jane, Roy, and Pam. The family’s unusual animal companions, a monkey named Mr Watson and a parrot called Joseph, add to the charm of the stories.

At the heart of The Cherrys is a simple but powerful idea: childhood is an adventure to be nurtured by imagination and shared experience. Rather than portraying children operating independently of adults, as was common in much children’s fiction of the era, these books emphasize active parental involvement, especially through the father figure, Captain Cherry. A retired explorer, he delights in creating games, puzzles, treasure hunts, mystery trails, and “happenings” that turn ordinary days into extraordinary quests. These events span coastlines, forests, gardens, and even indoor spaces transformed by imagination into jungles, deserts, or deserted islands.

The recurring concept of a “happening” – a structured, imaginative adventure, is one of the defining features of the series. Whether decoding maps, tracking mysterious figures, solving puzzles, or embarking on seaside explorations, each book presents a series of linked episodes that encourage curiosity, teamwork, problem-solving, and play. Scott’s approach reflects a belief in the value of learning through play, where the boundaries between fantasy and reality are fluid but always grounded in cooperative activity with family and friends.

Another important theme in The Cherrys is engagement with the natural and built environment. Scott often provided maps of the stories’ fictional settings , such as Market Cray or St Denis Bay, and used them as stages for the characters’ activities. This emphasis on place encourages readers to see their own landscapes as rich with potential for discovery. The stories also reflect a positive view of the mid-century British countryside and coast, celebrating local topography and community life.

Because Scott was writing at a time when much of children’s literature featured independent adventures without adults, The Cherrys stood out in its portrayal of grown-ups as co-adventurers rather than obstacles. This inclusive structure bridges the generational gap, showing children and adults working together, learning from one another, and finding joy in shared challenges.

Despite their popularity in their day, these books are no longer in print, making them a somewhat forgotten gem of 1950s and 1960s British children’s literature. Yet for those who discover them today, the series offers a window into a world where imagination, family bonds, adventure, and everyday wonder are woven seamlessly into the narrative fabric.