This spring, I’m trying something new, or perhaps, it’s something very old. I’m giving two of my 3’ x 8’ raised beds over to chaos. Not to neglect, but to intelligent disorder, a conscious step away from the regimented rows and into the wild wisdom of nature.

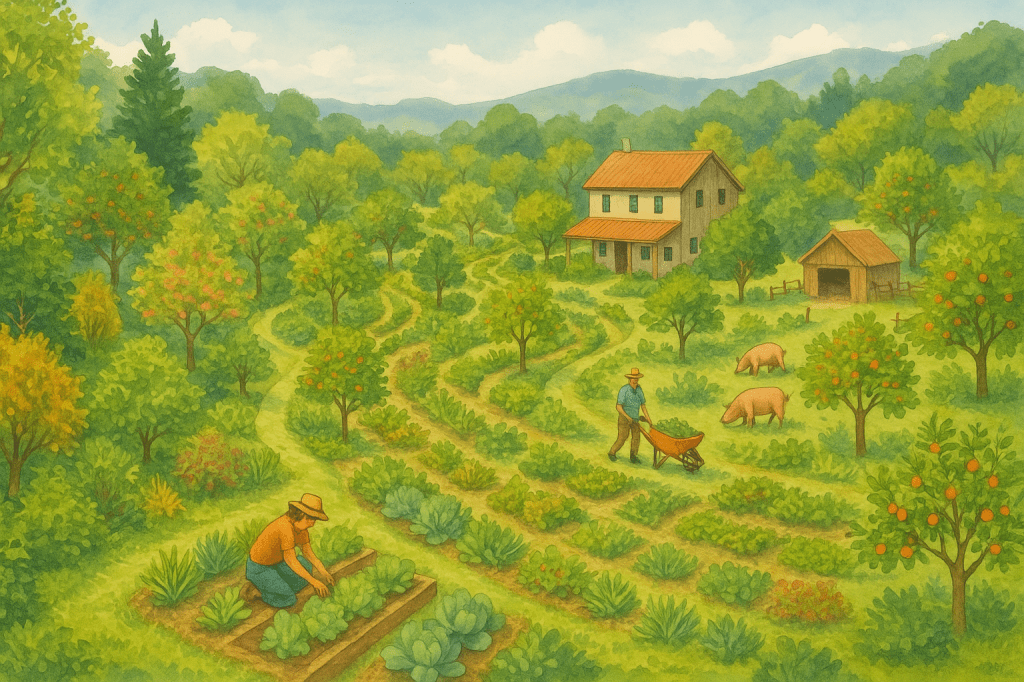

I’ve spent years designing gardens around principles of companion planting, guilds, crop rotation, and soil stewardship. These tools work, no doubt, but nature doesn’t plant in rows. She scatters. She layers. She invites diversity, and lets the strongest, most adaptive life flourish. And so, inspired by that, I’m preparing a chaos garden.

Here’s the plan: I’ve gathered a mixed jar of seed: vegetables, herbs, flowers, and a few rogue wild edibles that I’ve saved or collected over the years. Into it go radish, arugula, calendula, dill, kale, turnip, nasturtium, peas, and fennel. Some mustard for early leaves, some poppy for beauty, some chard for colour. Even a few tomato and squash seeds, just to see who wins the race.

I’ll loosen the soil, adding compost and manure, broadcast the mix by hand, rake it in gently, and water deeply. No rows. No labels. Just biodiversity in motion.

This kind of growing goes by many names: scatter planting, chaos gardening, even seed bombing when done guerrilla-style, but under the surface, it shares DNA with deeper systems thinking. It’s a living expression of polyculture, multiple species growing together in dynamic balance. It echoes permaculture’s ethic of cooperation with natural systems, and it sets the stage for self-seeding gardens, where plants aren’t just harvested, they’re invited to return.

Why do this?

First, because diversity builds resilience. Different plants fill different niches. Deep roots break soil; shallow roots hold moisture. Nitrogen fixers support leafy greens. Leafy greens shade the soil. Flowering herbs call in predators that keep pests in check.

Second, because it discourages monoculture pests and weeds. If you can’t find a pattern, neither can the cabbage moth.

Third, because it invites observation. I don’t know what will thrive, but I know I’ll learn something from what does.

And finally, because it’s joyful. There’s a delight in surprise, in watching an ecosystem unfold in real time, unbound by our expectations.

I won’t intervene much. I’ll harvest what’s ready, let the rest go to seed, and see what returns next year. My role is less conductor, more steward. Less controller, more curious partner.

I still have my perennial fruit and vegetables scattered across the hobby farm using permaculture layers, so I won’t be going hungry if the chaos fails to produce.

In a world obsessed with order and output, these little beds will be a place of play, experimentation, and ecological trust. A microcosm of what happens when we let go, just a bit, and let the land speak back.

If you’re curious about trying this yourself, start small. Choose a bed or even a large container. Use what you have, and most of all, resist the urge to overthink it. Nature knows what to do.

This is the season I choose to sow chaos. I suspect it will be the most ordered thing I grow.

Here’s a curated list of vegetable, herb, and edible flower seeds well-suited for chaos planting in Canadian Hardiness Zone 5. These plants are generally fast-growing, cold-tolerant, or self-seeding—and they don’t mind a little competition.

Leafy Greens (Cut-and-Come-Again, Fast Growers)

These thrive in early spring/fall and often reseed:

• Arugula – spicy, fast to mature, great for pollinators when it flowers

• Lettuce (mixed looseleaf varieties) – tolerates partial shade, quick to sprout

• Mustard Greens – bold flavor, early spring/fall performer

• Tatsoi – cold-hardy Asian green, forms a rosette

• Mizuna – feathery leaves, handles crowding well

• Spinach – plant early; loves cool weather

Root Crops

These do surprisingly well when thinned during harvest:

• Radish – very fast, natural “row marker” and soil loosener

• Carrots – mix different colours/sizes for variety

• Turnip – dual-purpose (roots + greens)

• Beets – harvest baby greens or mature roots

• Rutabaga – slower to mature, tolerates cooler temps

Legumes (Nitrogen Fixers)

Support other plants and create vertical interest:

• Peas (sugar snap or shelling) – sow early, great for trellises or natural climbing

• Fava Beans – cold-tolerant and nitrogen-rich

• Bush Beans – not too tall, easy to scatter

Cabbage Family (Brassicas)

Pest-prone in rows, but thrive in mixed beds:

• Kale – resilient, frost-tolerant, often overwinters or self-seeds

• Pak Choi – fast-maturing and shade-tolerant

• Broccoli Raab – leafy with small florets, matures quickly

• Mustard – doubles as a trap crop for flea beetles

Herbs (Pollinator Magnets & Companion Plants)

They support insect diversity and natural pest control:

• Dill – attracts ladybugs and beneficial wasps

• Cilantro – bolts quickly, great for early pollinators

• Parsley – slower growing, useful kitchen herb

• Chervil – good for shade and cool conditions

Edible Flowers (Beauty + Function)

These help deter pests and support pollinators:

• Calendula – self-seeds easily, blooms early and long

• Nasturtiums – edible leaves and flowers, acts as aphid trap crop

• Borage – self-seeds readily, attracts bees

• Violas – small, edible blooms for salads

Others for Experimentation

A few crops that might surprise you:

• Swiss Chard – colourful, resilient, good for succession

• Zucchini or Pattypan Squash – use only a few seeds; they get large

• Cherry Tomatoes – some may thrive if your season is long enough

• Onions (green onions from seed) – slow, but good in dense plantings

Tips for Success in Zone 5 Chaos Planting

• Sow early in spring (as soon as the soil is workable)

• Choose cold-hardy or short-season varieties (mature in 50–70 days)

• Water evenly after sowing, then mulch lightly to retain moisture

• Harvest regularly and thin as needed, using what’s edible