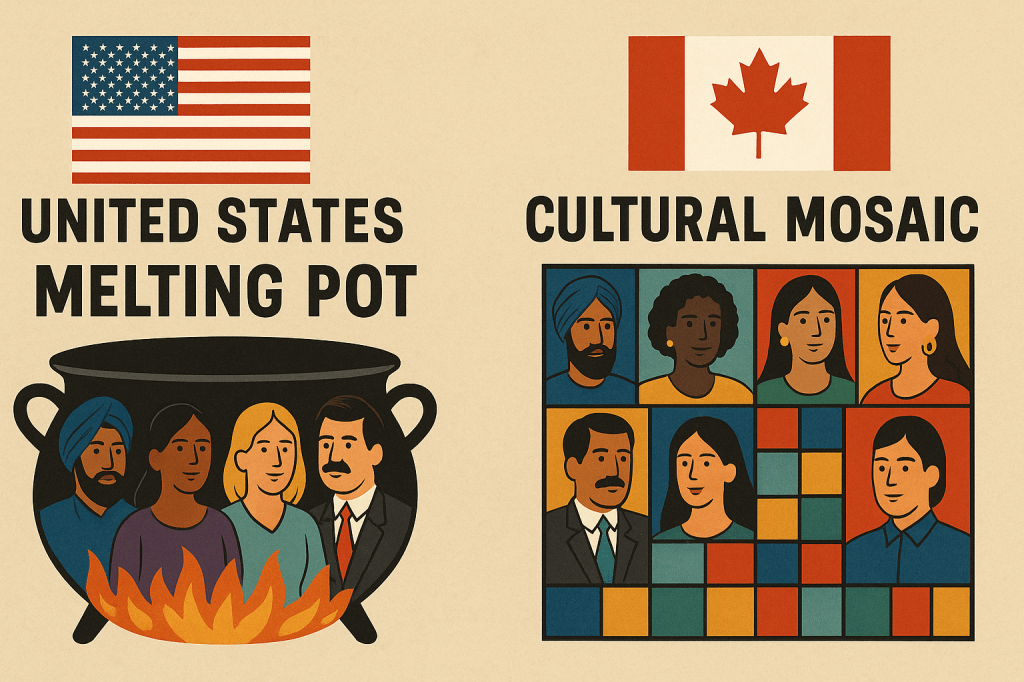

For over a century, the United States has proudly embraced the metaphor of the “melting pot,” a vision in which immigrants from all over the world come together to form a singular American identity. This idea suggests that while people may arrive with distinct languages, customs, and traditions, they are expected to assimilate into a common culture; one that prioritizes English, democratic values, and a shared national ethos. The melting pot is often framed as a symbol of unity, a place where differences dissolve in the service of a greater whole. However, this model has its critics, who argue that it pressures immigrants to abandon their unique cultural heritage in order to conform.

The roots of the melting pot concept can be traced back to Israel Zangwill, a British playwright whose 1908 play The Melting Pot romanticized America as a land where old ethnic divisions would fade away, forging a new, united people. While Zangwill gave the concept its famous name, the push for assimilation had been shaping U.S. policy and attitudes long before. Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president, was one of its most vocal proponents, arguing that immigrants must fully adopt American customs, language, and values to be considered truly American. The early 20th century saw the rise of the Americanization movement, which reinforced these ideas through public education, labor policies, and civic initiatives. By mid-century, the expectation of cultural conformity had become deeply embedded in American identity, influencing everything from language policies to popular media portrayals of immigrant life.

Canada, on the other hand, has cultivated a different metaphor, that of a “cultural mosaic.” Rather than seeking to merge all cultures into one, Canada actively encourages its people to maintain and celebrate their distinct identities. This approach is not just a social philosophy, but an official policy, first enshrined in 1971 with the introduction of the Multiculturalism Policy by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Unlike the American melting pot, which emphasizes assimilation, Trudeau’s vision was one of inclusion without erasure. His government recognized that Canada’s growing diversity, particularly from non-European immigration, required a shift in how the country defined itself.

The passage of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act in 1988, under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, further reinforced this philosophy by guaranteeing federal support for cultural communities, anti-discrimination measures, and the preservation of minority languages. Unlike the U.S., where English is seen as a central marker of national identity, Canada has long embraced bilingualism, officially recognizing both English and French. Additionally, Canada has extended support for Indigenous and immigrant languages in education and public services, further emphasizing its commitment to cultural pluralism.

The differences between these two models of integration are profound. In the United States, the expectation is often that newcomers will embrace “Americanness” above all else, whether that means speaking only English, adopting mainstream American customs, or minimizing their ethnic identity in public life. While the U.S. does recognize and celebrate diversity in some respects; Black History Month, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and the popularity of international cuisines all attest to this, there remains a strong undercurrent that to be truly American, one must fit within a specific cultural framework.

Canada’s approach, by contrast, views multiculturalism as a strength rather than a challenge to national unity. Cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal are known for their ethnic neighborhoods, where different cultures not only survive, but thrive. Unlike the American approach, which often treats diversity as something to be managed or assimilated, Canada has built institutions that actively encourage it. Government funding for cultural festivals, multilingual public services, and policies that allow dual citizenship all reflect a belief that preserving one’s cultural roots does not weaken Canadian identity, but enriches it.

This difference is especially clear in the way both countries handle language. In the U.S., English is often seen as the primary marker of integration, with political debates regularly emerging over whether Spanish speakers should make greater efforts to assimilate linguistically. Canada, meanwhile, has long recognized both English and French as official languages, and has even extended support for Indigenous and immigrant languages in education and public services.

Ultimately, the American melting pot and the Canadian cultural mosaic reflect two very different visions of national identity. While the U.S. values unity through assimilation, Canada finds strength in diversity itself. Neither model is without its challenges, but the contrast between them speaks to fundamental differences in how these two North American nations define what it means to belong.