In the unfolding geopolitical drama of the early 2020s, Canadians have found themselves wrestling with a deep and persistent question: what does it mean to be loyal to Canada? To what extent does loyalty bind us to our values, our institutions, and our sovereignty – particularly when the world’s sole superpower stands at our doorstep with both trade leverage and military might?

This question has never been more acute than in the political struggles surrounding the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) and its relationship with Canadian identity.

The Political Landscape – A Crossroads of Loyalty and Identity

Recent polling has shown that Canadians overwhelmingly believe in protecting and promoting a distinct Canadian identity. Fully 91 percent of respondents say it’s important to protect Canada’s culture and identity, particularly vis-à-vis the influence of the United States. Canadian stories, language, and cultural autonomy matter deeply to the electorate. A similar share also insists the national creative sector should be actively supported as a means of preserving this identity.

Yet, even with this firm sense of national self-definition, the Conservative Party struggles to align itself with these sentiments in a way that resonates broadly outside its core base. National polls show the Liberals under Mark Carney consistently leading or tied with the Conservatives, and importantly, Canadians trust Carney more than Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre to manage Canada–U.S. relations and economic sovereignty issues like tariffs.

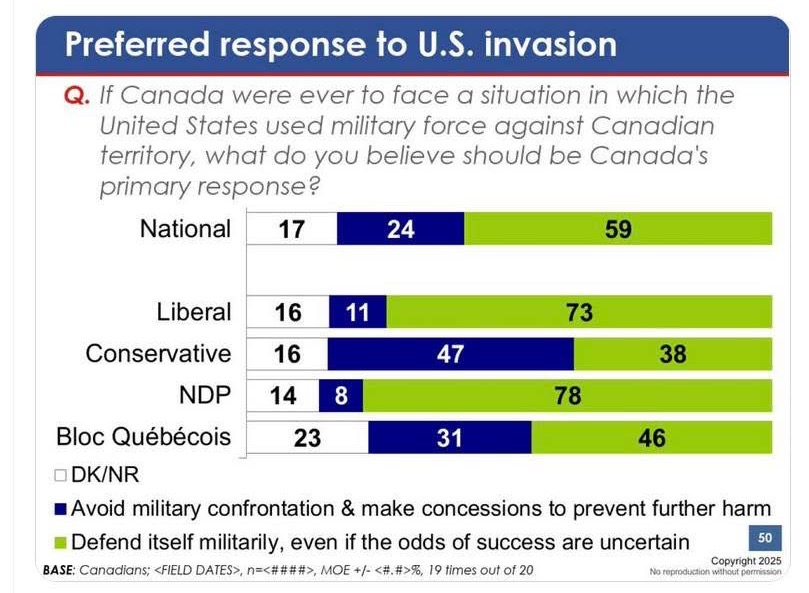

In the context of rising public skepticism about American intentions and influence, this is no small matter. A recent global polling story highlighted dramatically worsening views of the United States among Canadians, with distrust of U.S. economic policy and fears about sovereignty now outpacing favourability.

The Conservative Identity Challenge

The CPC’s dilemma is systemic and layered. On one hand, it portrays itself as staunchly nationalistic and protective of Canadian freedom – championing economic independence, smaller government, and opposition to what it frames as overreach by federal elites. Official party surveys and promotional material heavily emphasise “Canada first” language and attack policies of political opponents as un-Canadian.

On the other hand, broader national polling suggests a paradox: supporters of the CPC are more likely than others to distrust national institutions, such as electoral outcomes – with only 44 percent of Conservative voters expressing confidence in election results, compared with much higher trust among Liberal voters.

Here we find the heart of a fissure: many Conservative voters affirm a version of Canada that rejects established institutions and narratives – yet this rejection can look less like loyalty to Canada and more like resentment toward perceived elite power structures. It’s a version of loyalty that is conditional and oppositional rather than unifying.

Moreover, recent polling data has shown that a substantial portion of Canadians – including those outside the CPC base – see the party as indistinguishable from its previous configurations, suggesting it struggles to redefine itself as a uniquely Canadian force rather than a continuation of old alliances.

The Cultural Divide Within Canadian Conservatism

Part of the CPC problem lies in how loyalty is framed internally versus how it is perceived externally. Within the party, messaging frequently leans on cultural grievances and critiques of “woke orthodoxy,” federal deficits, or immigration policy, rather than building a positive vision of nationhood that embraces the multicultural, bilingual, and globally engaged Canada most Canadians cherish.

For voters outside the core base – notably in Quebec and among women – this framing can feel alienating. Polling shows the CPC has struggled to gain traction in Quebec, where its support has often remained well below national averages. Conservative messaging themes that work in parts of Alberta or the Prairies – economic libertarianism or cultural backlash – do not translate easily into a unifying vision of what it means to be Canadian in a diverse and interconnected country.

Loyalty to Canada vs. Loyalty to a Movement

This sets up a crucial distinction: Is the CPC loyal to Canada as an ideal and as a state, or is it loyal to a particular movement that sees Canada through the lens of grievance politics?

Among many Canadians, loyalty to the nation is less about opposition and more about protection and stewardship of the Canadian project. This includes safeguarding institutions, promoting cultural sovereignty, navigating global power dynamics with nuance, and articulating a sense of shared belonging. That broader, more inclusive sense of national loyalty appears more readily embodied by leaders seen as centrist or unifying – such as Carney in recent polls – than by those perceived as divisive or reactive.

The Conservative Paradox of Canadian Belonging

The CPC today stands at a historic crossroads: it must reconcile its internal identity and base-motivated framing with a broader, more inclusive conception of Canadian loyalty and citizenship. To succeed nationally, the party will need to articulate a vision of Canada that brings together sovereignty, dignity, diversity, and institutional trust – rather than simply opposing the incumbent government or elite institutions.

In the end, the challenge of the CPC is not a lack of patriotism among its members, but rather a fractured conception of what Canadian loyalty means in an era of global tension and domestic diversity – a tension that mirrors the very paradox Canadians are wrestling with: Can one be loyal to Canada while also questioning its structures? The answer will define not just the future of a political party, but the future of Canadian national identity itself.