In the grand pantheon of Star Trek mysteries; why redshirts never survive, why Klingon foreheads changed mid-century, why nobody uses seatbelts on the bridge, one lesser-discussed, but utterly maddening question remains: Why is programming new food into the replicator such a colossal pain in the nacelles?

I mean, come on. This is a civilization that can fold space, beam people across hostile terrain, and host full Victorian murder mysteries in the holodeck with better lighting than a BBC costume drama. And yet, when someone wants to add their grandmother’s secret tomato sauce recipe to the replicator, it’s a whole saga. Suddenly you need a molecular biologist, a culinary technician, and probably Counselor Troi to help you process your feelings about spice levels.

Let’s break this down. Replicators are based on the same matter-energy conversion technology that powers transporters. They take raw matter, usually stored in massive energy buffers, and rearrange it into whatever pattern you’ve requested, be it a banana, a baseball bat, or a bust of Kahless the Unforgettable. On paper, it’s magical. Infinite possibilities. Want a rare Ferengi dessert that was outlawed in six systems? No problem, if it’s in the database.

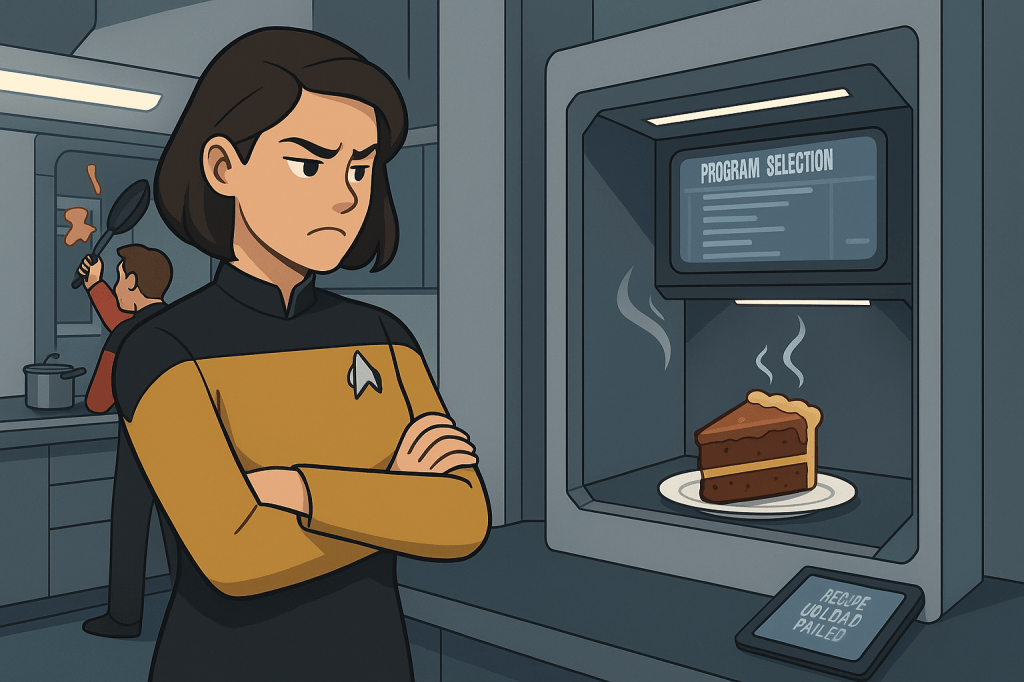

But here’s the catch: the database. That’s the real villain of the piece. Everything has to be pre-programmed. And programming something new isn’t as simple as chucking a muffin into the transporter and yelling “Make it so.” Why not? Because food is astonishingly complex.

Sure, from a chemical standpoint, you can break a slice of chocolate cake down into carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, the same building blocks the replicator can access, but that’s like saying Shakespeare’s Hamlet is just twenty-six letters arranged in a particular order. The cake is more than its ingredients. It’s texture, mouthfeel, flavor balance, aroma. It’s how the icing melts just slightly faster than the sponge in your mouth. It’s memory, emotion – it’s nostalgia on a fork.

And the replicator, bless it, just doesn’t do nuance.

In-universe, we’ve seen Starfleet crews struggle with this time and again. Captain Sisko flatly refuses to eat replicated food, relying instead on traditional cooking, partly because he loves the craft, but also because the replicator’s version of jambalaya “tastes like it was programmed by someone who’s never even seen a shrimp.” Over on Voyager, Neelix throws himself into galley work precisely because replicated food gets old fast, especially when you’re lost in the Delta Quadrant with no fresh supplies, and morale hanging by a thread.

Programming a new recipe means getting the proportions right, inputting molecular structures, and testing the end result, again and again, for taste, safety, and cultural appropriateness. You want Klingon bloodwine that doesn’t melt the replicator coils? Better spend a few days in the ship’s chem lab. There’s no “scan dish” function, because full transporter-level molecular scans are expensive, dangerous, and, frankly, overkill for your aunt’s chicken pot pie.

Not to mention the ethical implications. Transporters work by disassembling matter at the subatomic level and reassembling it elsewhere. That’s fine when you’re moving Lieutenant Barclay to Engineering (again), but doing a transporter-level scan of organic matter for replication purposes raises thorny questions: if you scan and replicate a living steak, is it alive? Is it conscious? Does it have legal rights under Federation bioethics law? You laugh, but remember, this is the same universe where holograms occasionally demand civil liberties.

So Starfleet plays it safe. Replicators are deliberately limited to lower-resolution blueprints, safe patterns, and tried-and-tested food profiles. They’re designed to be efficient, not perfect. And while that keeps the ship’s energy budget in check and prevents any Frankensteinian chowder accidents, it also means the food sometimes tastes like packing peanuts soaked in nostalgia.

Yet, maybe that’s the beauty of it. In a post-scarcity world where you can have anything at the touch of a button, authenticity becomes the rare commodity. Cooking, real cooking, becomes an act of love, tradition, identity. When Picard orders “tea, Earl Grey, hot,” he’s not looking for a proper British brew; he’s summoning comfort, consistency, something almost ritual. When Riker burns an omelet trying to impress a crewmate, it’s not because he lacks tech, it’s because he values the experience, the attempt.

So no, the replicator can’t just scan the damn cake. And maybe that’s a good thing. Because in a galaxy of warp drives and wormholes, the things that make us human: taste, culture, connection, still require effort. A pinch of spice. A dash of imperfection, and maybe, just maybe, a reminder that sometimes the best things can’t be replicated.

At least not without a food fight in the galley.