Canada has long built its agri-food reputation on food safety and quality. Rigorous inspection systems, traceability protocols, and high sanitation standards have made Canadian products trusted both domestically and on the global market. But while these strengths remain critical, they are no longer sufficient. In an era of accelerating climate disruption, geopolitical instability, supply chain fragility, and rising inequality, Canada must now turn its focus to food security – the guarantee that all people, at all times, have reliable access to enough affordable, nutritious food.

Food safety ensures that the food we consume is free from contamination. Food quality ensures it meets certain standards of freshness, nutrition, and presentation. These are the cornerstones of consumer trust. Yet, neither concept addresses the structural risks facing our food system today. Food security asks a different set of questions: Can Canadian households afford the food they need? Can our food system withstand climate shocks, trade disputes, and infrastructure breakdowns? Are our supply chains inclusive, decentralized, and flexible enough to adapt to major disruptions?

Recent events have underscored the fragility of our current system. During the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions to cross-border trucking and meat processing plants exposed just how centralized and brittle key segments of Canada’s food supply have become. In British Columbia, floods in 2021 cut off rail and road access to Vancouver, leading to supermarket shortages within days. In the North and many Indigenous communities, chronic underinvestment has made access to affordable, fresh food unreliable at the best of times, and catastrophic during crises.

Moreover, food insecurity is rising, not falling. In 2023, over 18 percent of Canadian households reported some level of food insecurity, with that number climbing higher among single mothers, racialized Canadians, and people on fixed incomes. Food banks, once seen as emergency stopgaps, are now regular institutions in Canadian life. This is not a failure of food safety or quality. It is a failure of access and equity – core dimensions of food security.

Part of the problem lies in how Canada conceptualizes its agri-food system. At the federal level, agriculture is still often framed as an export sector rather than a foundational pillar of domestic well-being. Policy is shaped by trade metrics, not food sovereignty. We excel at producing wheat, pork, and canola for overseas markets, but remain heavily reliant on imports for fruits, vegetables, and processed goods. Controlled-environment agriculture remains underdeveloped in most provinces, leaving the country vulnerable to droughts, supply chain blockages, and foreign policy flare-ups.

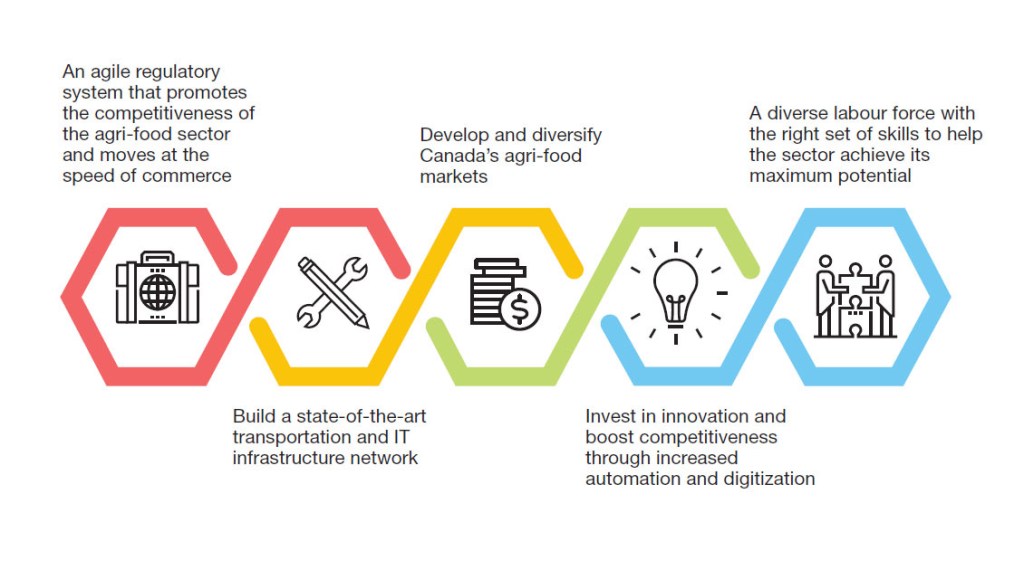

To move toward food security, Canada must first reframe its priorities. This means investing in local and regional food systems that shorten supply chains and embed resilience close to where people live. It means modernizing food infrastructure: cold storage, processing capacity, and distribution networks, particularly in underserved rural and northern communities. It means supporting small and medium-scale producers who can provide diversified, adaptive supply within regional ecosystems. It also means integrating food policy with social policy. Income supports, housing, health, and food access are intertwined. Any serious food security strategy must address affordability alongside production.

Several provinces have begun to lead. Quebec has developed a coordinated framework focused on food autonomy, greenhouse expansion, regional processing, and public education. British Columbia is experimenting with local procurement strategies and urban farming initiatives. But the federal government has not yet articulated a cohesive national food security agenda. The 2019 Food Policy for Canada set out promising goals, but lacked the legislative weight and funding to shift the structure of the system itself.

Now is the time to act. Climate events will increase in frequency and severity. Global trade dynamics are growing more volatile. Technological transformation and consumer expectations are evolving rapidly. A resilient, secure food system cannot be improvised in moments of crisis. It must be designed, invested in, and governed intentionally.

Canada’s record on food safety and quality is a strength to build on. But it is not enough. Food security is the challenge of this decade. Meeting it will require a new policy imagination, one that centres equity, redundancy, and sustainability as the foundations of a food system truly built to serve all Canadians.