For years, Canada’s ambitious dream of linking its greatest cities with true high-speed rail has hovered in the realm of feasibility studies and future pipe dreams. Now, in the closing weeks of 2025, that dream has shifted decidedly toward reality; not because steel is yet being laid, but because the Alto high-speed rail initiative has crossed a crucial threshold from concept to concerted preparation and public engagement.

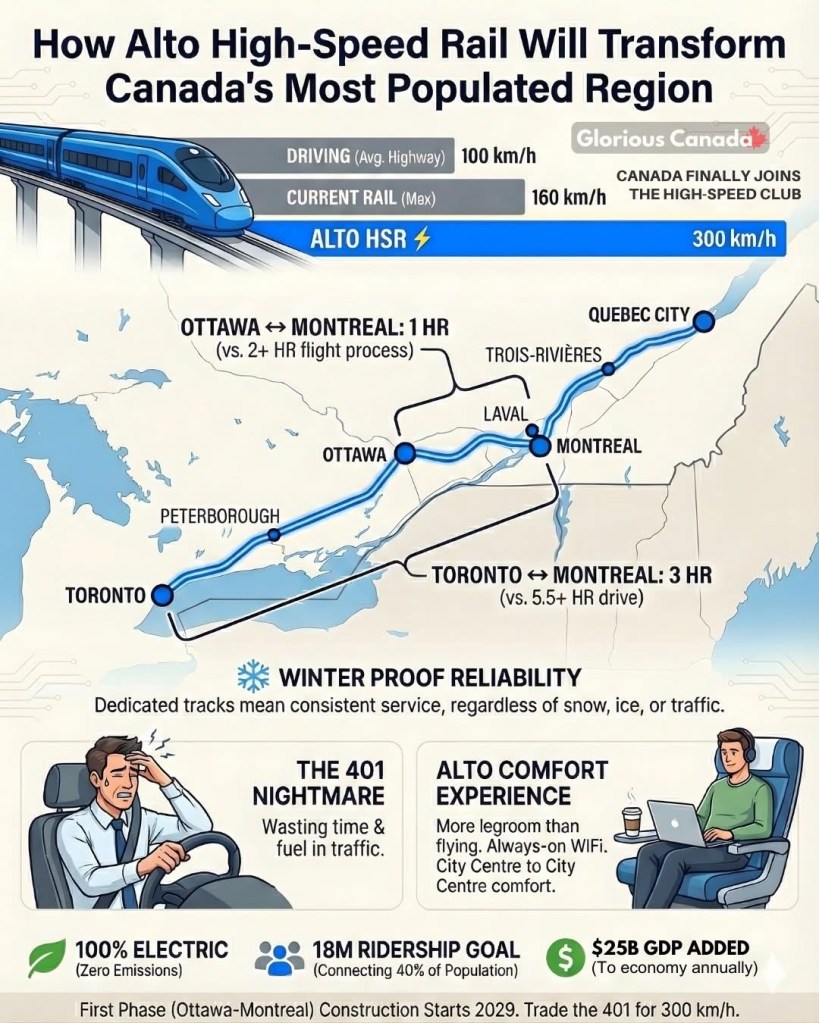

At its core, Alto is a transformative infrastructure vision: a 1,000-kilometre electrified passenger rail network connecting Toronto to Québec City with trains capable of 300 km/h speeds, slicing travel times compared to what today’s intercity rail offers and binding half the nation’s population into a single, rapid mobility corridor. The design phase, backed by a multi-billion-dollar co-development agreement with the Cadence consortium, is well underway, and the federal government has signaled its intent to see this project delivered as one of the largest infrastructure investments in decades.

The most noteworthy milestone in recent weeks has been a strategic decision about where Alto will begin to take physical shape. On December 12, officials announced that the Ottawa–Montreal segment – roughly 200 km – will be the first portion of the network to advance toward construction, with work slated to begin in 2029. This choice reflects a practical staging strategy: by starting with a shorter, clearly defined corridor that spans two provinces, engineering and construction teams can mobilize simultaneously in Ontario and Québec and begin delivering economic and skills-development benefits sooner rather than later.

This announcement isn’t just about geography; it marks a shift in Alto’s progression from broad planning to community-level engagement. Beginning in January 2026, Alto will launch a comprehensive three-month consultation process that includes open houses, virtual sessions, and online feedback opportunities for Canadians along the corridor. These sessions will inform critical decisions about alignment, station locations, and mitigation of environmental and community impacts. Indigenous communities, municipalities, and public institutions will be active participants in these discussions as part of Alto’s ongoing commitment to consultation and reconciliation, a recognition that this project’s success hinges not only on engineering prowess, but on thoughtful, inclusive planning.

Beyond route planning, Alto and Cadence are also turning to Canada’s industrial capacity, particularly the steel sector, to gauge the domestic supply chain’s readiness for what will undeniably be a massive procurement exercise. With thousands of kilometres of rail and related infrastructure components needed, early outreach to the steel industry is intended not just to assess production capacity, but to maximize Canadian content and economic benefit from the outset.

Yet not every question has a definitive answer. Strategic discussions continue over the optimal location for Alto’s eventual Toronto station, with the CEO publicly acknowledging that a direct connection to Union Station may not be guaranteed; a decision that could shape ridership patterns and integration with existing transit networks across the Greater Toronto Area.

As the calendar turns toward 2026, the Alto project sits at an inflection point: one foot firmly planted in detailed design and consultation, the other inching closer to the realm of shovels and steel rails. Political support appears robust, and fiscal planning, including major project acceleration initiatives and supportive legislation, has built momentum. Yet, as any transportation planner will tell you, the distance between planning and construction is long, often winding, and frequently subject to political, economic, and community pressures.

Still, for advocates and observers alike, the significance of the latest developments cannot be overstated. Alto has graduated from “what if?” to “when and how,” and that alone marks a major step forward in Canada’s transportation evolution.