Having lived on four continents, I have always found myself drawn to smaller and smaller communities for my home. Although I currently reside just 45 minutes from a capital city of one million, my daily life unfolds in a town of fewer than 15,000, where infrastructure is well maintained, and population growth remains manageable. However, the same cannot be said for the world’s larger cities, which struggle to keep pace with rapid urbanization, strained public services, and crumbling infrastructure. As populations surge, these cities face mounting challenges in housing affordability, traffic congestion, environmental sustainability, and social inequality. The pressure to expand services while maintaining quality of life grows ever more daunting, forcing urban planners to grapple with complex solutions that balance progress with livability.

As I said, major cities face persistent challenges in maintaining infrastructure, particularly transportation networks. The costs of managing traffic, repairing roads, and ensuring safe mobility place heavy demands on municipal budgets. However, cities also generate significant financial returns, primarily through commercial property taxes. Businesses cluster in urban centers to take advantage of high foot traffic and workforce access, providing a steady revenue stream that supports public services and infrastructure.

Commuters further strengthen this economic engine. While they may reside in surrounding suburbs, their workdays are spent in the city—eating at restaurants, shopping, and using local services. Their daily spending injects revenue into businesses, which in turn contributes to the city’s tax base. This dynamic allows large cities to maintain economic vitality without solely depending on residential tax revenue. The cycle of investment and reinvestment enables cities to expand and modernize infrastructure, accommodating growing populations and business activity.

What Is the Ideal City Size?

There is no universal “optimal” city size, as a community’s efficiency depends on geography, economic function, and resident needs. However, research suggests that mid-sized cities (50,000–100,000 residents) often strike the best balance between economic diversity and infrastructure manageability. They offer a strong mix of job opportunities, public services, and cultural amenities while avoiding the congestion and financial strain of major metropolitan areas. Additionally, studies have linked this population range to higher rates of civic engagement and even better athletic development, as mid-sized towns tend to produce more professional athletes per capita than larger cities.

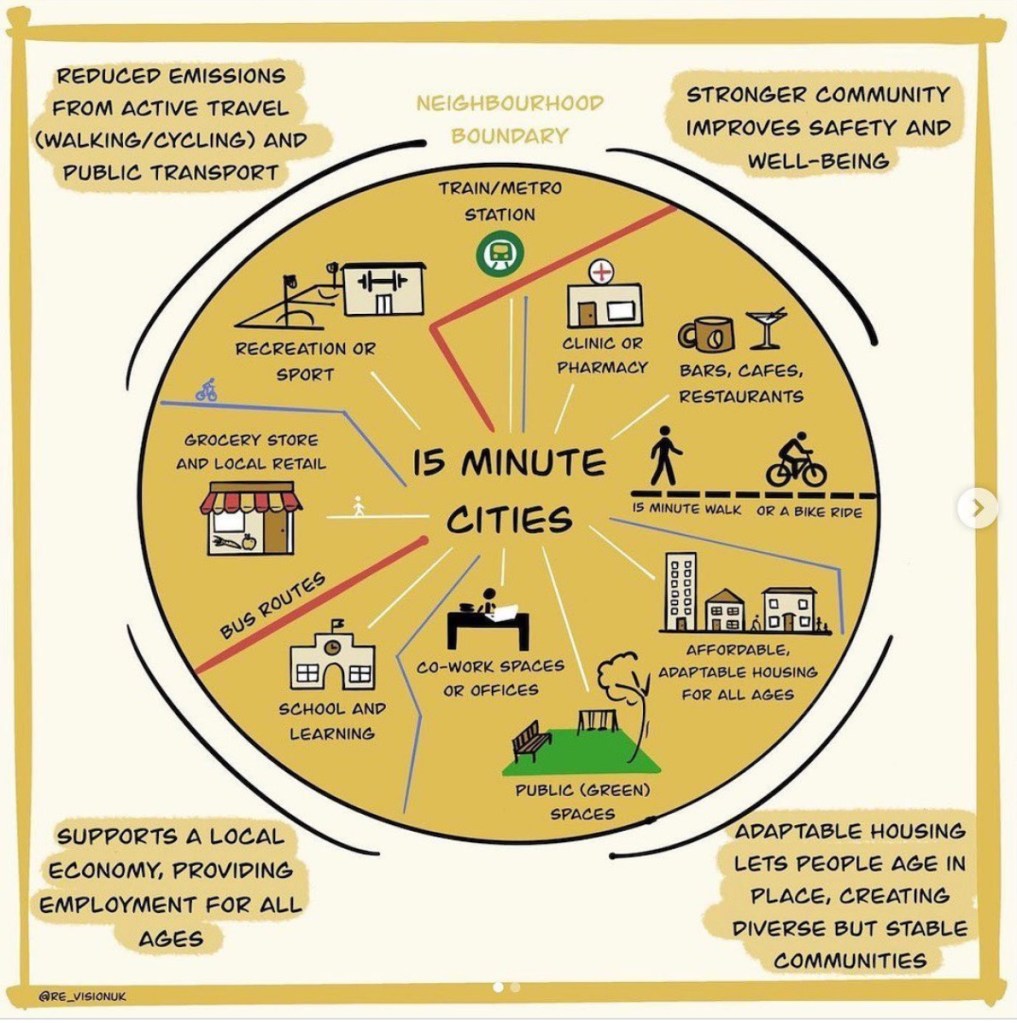

Smaller-scale planning models, such as New Urbanism, advocate for compact, walkable neighborhoods of 10,000–30,000 residents. These communities emphasize mixed-use development, local amenities, and reduced car dependency—design elements that promote both economic activity and social cohesion. At an even smaller scale, research on human social networks suggests that communities of around 150 people optimize social bonds, creating close-knit environments where personal relationships thrive.

Ultimately, sustainable urban planning requires balancing economic opportunities with infrastructure capacity. While larger cities offer broa job markets and cultural diversity, mid-sized and smaller communities often provide a stronger sense of connection, lower living costs, and a more manageable scale of development.

When Big Cities Outgrow Their Tax Base

As major cities expand, their infrastructure demands often surpass what local tax revenues can support. Even in high-tax environments like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, the financial burden of maintaining transit systems, utilities, and social services outstrips property and business tax income. The situation is further complicated by the growing demand for affordable housing, healthcare, and education, which places additional strain on municipal budgets.

This challenge is not unique to North America. Global cities such as London and Tokyo face similar struggles, often resorting to controversial funding measures like congestion pricing, privatization of public services, or reliance on state and federal subsidies. The result is an ongoing cycle of deferred maintenance, rising public debt, and political pressure to either cut services or increase taxation.

To address this imbalance, urban planners increasingly advocate for decentralization—shifting growth toward smaller regional centers to distribute population and economic activity more evenly. Encouraging mid-sized cities to absorb a greater share of development could relieve pressure on overstretched metropolitan areas while fostering more sustainable and resilient urban landscapes. By investing in infrastructure and economic incentives outside major cities, governments can create a more balanced and efficient urban network that benefits a broader population.