When I wrote Please, Not Another Old White Male Academic just over a year ago, my concern was not personal. It was structural. Canada has a long and slightly embarrassing habit of confusing résumé gravity with political imagination. We import seriousness, assume competence, and hope charisma follows later.

Mark Carney, at that moment, looked like the distilled essence of that habit.

Former Governor of the Bank of Canada. Former Governor of the Bank of England. A man fluent in balance sheets, risk curves, and global capital flows. Almost entirely untested in the messy, adversarial, human business of electoral politics.

And yet, what followed matters.

Carney did not simply arrive in the Prime Minister’s Office as a caretaker technocrat. He won the Liberal leadership race, became Prime Minister as leader of the governing party, and then did the one thing that ultimately separates legitimacy from convenience in a parliamentary democracy.

He went to the country.

And he won.

That sequence, leadership first and electoral endorsement second, has shaped everything that followed.

From Leadership to Mandate

Leadership races create prime ministers. Elections create authority.

Carney’s leadership victory gave him the keys. The federal election that followed gave him something far more important: permission. Permission to act, to break with inherited orthodoxies, and to absorb political damage without immediately losing his footing.

This matters because much of what Carney has done in his first year would have been politically untenable without a fresh mandate.

Ending the consumer carbon pricing regime, for example, was not a technocratic adjustment. It was a cultural intervention in a debate that had become symbolic rather than functional. That decision would have been framed as betrayal had it come from an unelected interim leader. Coming from a Prime Minister who had just won an election, it landed differently.

Not quietly. Not universally. But legitimately.

The First Act: Clearing the Political Air

Within weeks of taking office following the election, Carney’s government dismantled the consumer-facing carbon tax. He did not do so by denying climate change or disavowing past commitments. He did it by acknowledging an uncomfortable truth: the policy had stopped working politically, and therefore had stopped working at all.

Carbon pricing had become a proxy war for identity, region, and class. Carney chose to remove it from the centre of the national argument, not because it was elegant, but because it was paralysing.

Shortly thereafter came the One Canadian Economy Act, a legislative attempt to dismantle internal trade barriers and accelerate nationally significant infrastructure by streamlining regulatory approvals. Supporters called it overdue modernization. Critics warned of environmental dilution and federal overreach.

Both readings were accurate.

What distinguished this moment was not the policy itself, but the confidence behind it. Carney was governing like a man who believed the election had granted him room to manoeuvre.

Trade Policy and the Post-Deference Canada

The same pattern appeared in foreign and trade policy.

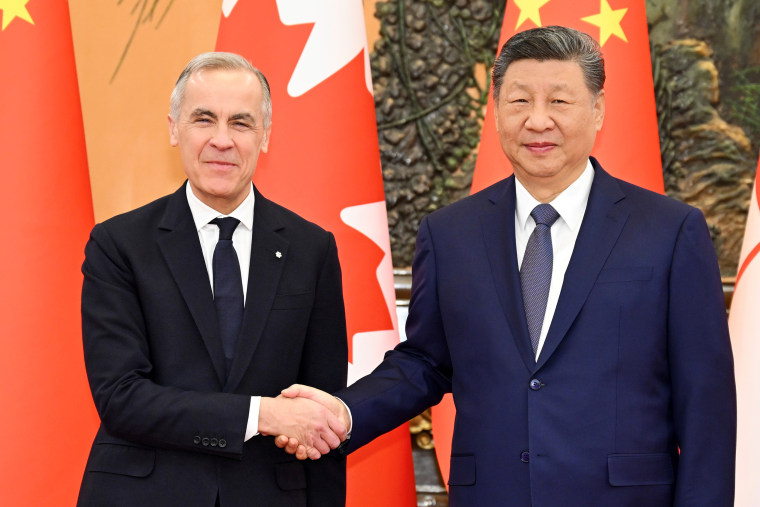

The tariff reset with China, including reduced duties on electric vehicles and reciprocal relief for Canadian agricultural exports, signaled a meaningful shift. Canada under Carney is less deferential, less reactive, and more openly strategic.

This was not an abandonment of allies. It was an acknowledgment of vulnerability.

Carney understands that Canada’s economic exposure to U.S. political volatility is no longer theoretical. Trade diversification, even when uncomfortable, has become a national security issue. That logic is straight out of central banking, but it now animates Canadian diplomacy.

Again, this is where the election mattered. A Prime Minister who had just won a national contest could afford to irritate orthodoxies that an unelected leader could not.

Climate Policy Without Rituals

Perhaps the most jarring shift for longtime observers has been Carney’s approach to climate.

This is a man who helped embed climate risk into global financial systems. His retreat from consumer-facing climate rituals has therefore confused many who expected moral consistency rather than strategic recalibration.

But Carney is not governing as an activist. He is governing as a systems thinker.

Industrial emissions, supply chains, energy infrastructure, and capital allocation matter more than behavioural nudges. He appears willing to trade rhetorical clarity for structural leverage, even at the cost of alienating parts of the environmental movement.

His cautious thaw with Alberta, including openness to regulatory reform and transitional infrastructure, reflects this same calculus. Climate transition, in Carney’s view, cannot be imposed against the grain of the federation. It must be engineered through it.

That is not inspiring. It may be effective.

Domestic Governance: Quiet by Design

Domestically, Carney’s first year has been notably untheatrical.

There have been targeted tax changes, a more disciplined capital budgeting framework, industrial protections in politically sensitive sectors, and modest expansions of labour-linked social supports. None of this screams transformation.

That restraint is intentional.

Carney governs like a man who believes volatility is the enemy. He does not seek to dominate the news cycle. He seeks to stabilize the operating environment. For supporters craving vision and opponents hunting scandal, this has been unsatisfying.

For a country exhausted by performative politics, it may be precisely the point.

Switzerland, the G7, and a Doctrine Emerges

Carney’s remarks in Switzerland this week and Canada’s hosting of the G7 crystallized what has been quietly forming all year.

Canada now has a governing doctrine.

It assumes a fragmented world. It rejects nostalgia for a rules-based order that no longer functions as advertised. It prioritizes resilience, diversification, and coordination among middle powers.

This is not moral leadership. It is strategic adulthood.

And again, it is enabled by the fact that Carney is not merely a party leader elevated by caucus arithmetic. He is a Prime Minister endorsed by voters, however imperfectly and however provisionally.

What I Got Wrong, and What Still Worries Me

I was wrong to assume Mark Carney would be inert.

But I remain uncertain that technocratic competence alone can sustain democratic consent. Systems thinkers often underestimate the emotional dimensions of legitimacy. Elections grant authority once. Narratives sustain it over time.

Carney has the former. He is still building the latter.

A year in, it is clear that he is not another placeholder academic passing through politics. He is attempting something more difficult and more dangerous: governing Canada as it actually exists, not as it nostalgically imagines itself to be.

Whether that earns him longevity will depend less on markets or multilateral forums, and more on whether Canadians come to see themselves reflected in his project.

Competence opened the door.

Winning the leadership gave him power.

Winning the election gave him permission.

What he does with that permission is the real story now.