There is a certain comforting myth Canadians like to tell themselves about the North. That sovereignty is something you declare, map, and defend with the occasional patrol and a strongly worded statement. It is a tidy story. It is also no longer true.

The Arctic is changing faster than our habits of thought. Ice patterns are less predictable, shipping seasons are longer, and great powers are no longer treating the polar regions as distant margins. They are treating them as operating environments. In that context, the Royal Canadian Navy’s quiet exploration of heavy, ice-capable amphibious landing ships deserves far more public attention than it has received.

These would not be symbols. They would be tools.

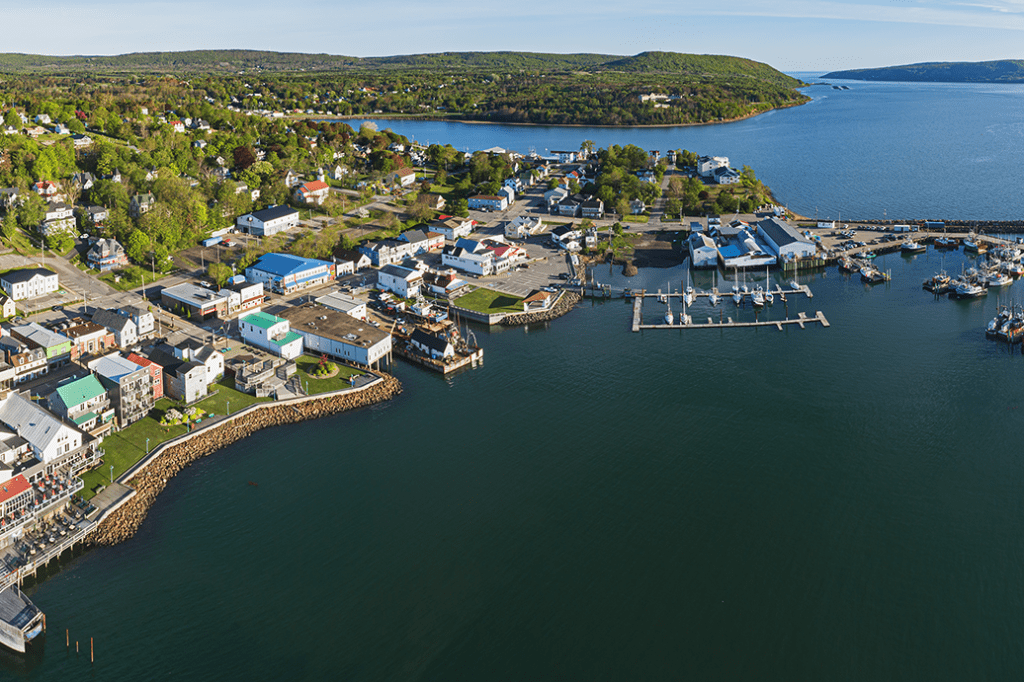

The idea is straightforward. Build Polar Class 2 amphibious ships capable of breaking ice, carrying troops and vehicles, and landing them directly onto undeveloped shorelines. In other words, floating bases that can operate independently across the Arctic archipelago, where ports are rare, airfields are limited, and weather regularly laughs at planning assumptions made in Ottawa.

This matters because Canada’s Arctic problem has never been about law. It has always been about logistics.

We claim a vast northern territory, but our ability to operate there is thin, seasonal, and fragile. We fly in when we can, sail in when ice allows, and leave when winter asserts itself. Presence is episodic. Capability is constrained. Persistence is mostly aspirational.

Russia, by contrast, has spent decades building the unglamorous machinery of Arctic power. Ice-strengthened amphibious ships. Heavy logistics vessels. A fleet designed not to visit the Arctic but to live in it. This is not about imminent conflict. It is about what serious states do when they intend to control their operating environment.

A Canadian Arctic mobile base would change the conversation. It would allow the movement of troops, Rangers, equipment, and supplies without waiting for ports that do not exist. It would support disaster response, search and rescue, medical care, and environmental protection in regions where help currently arrives late or not at all. It would give commanders options that do not depend on fragile airlift chains or ideal weather windows.

Just as importantly, it would allow Canada to stay.

Polar Class 2 capability is the dividing line between symbolism and seriousness. These ships could operate year-round in heavy ice, not just skirt the edges of the season. That is what credibility looks like in the Arctic. Not constant activity, but the unquestioned ability to act when required.

There is also a domestic dimension that should not be dismissed. Designing and building these vessels in Canadian shipyards would deepen national expertise in Arctic naval architecture and ice operations. It would anchor the National Shipbuilding Strategy in future capability rather than replacement alone. Sovereignty is reinforced when a country can design, build, crew, and sustain the tools it needs for its own geography.

None of this is cheap or easy. Crewing will be difficult. Sustainment will be demanding. Political patience will be tested the first time costs rise or timelines slip. That is always the case with real capability, which is why symbolic alternatives are so tempting.

But the alternative path is well worn and well known. Light patrol ships. Seasonal deployments. Carefully photographed exercises. Earnest speeches about the North delivered from comfortable distances.

At some point, a country has to decide whether its Arctic is a talking point or a responsibility.

Amphibious, ice-capable ships are not about militarizing the North. They are about acknowledging reality. The Arctic is not becoming less important. It is becoming more accessible, more contested, and more consequential. Sovereignty, in that world, is not what you say. It is what you can do, consistently, in all seasons.

The North does not need grand gestures. It needs presence that endures.