If Part One exposes the fiction of automatic alliance protection, Part Two must confront a harder truth. The absence of a military response does not require submission. This is not 1938, and restraint need not mean appeasement.

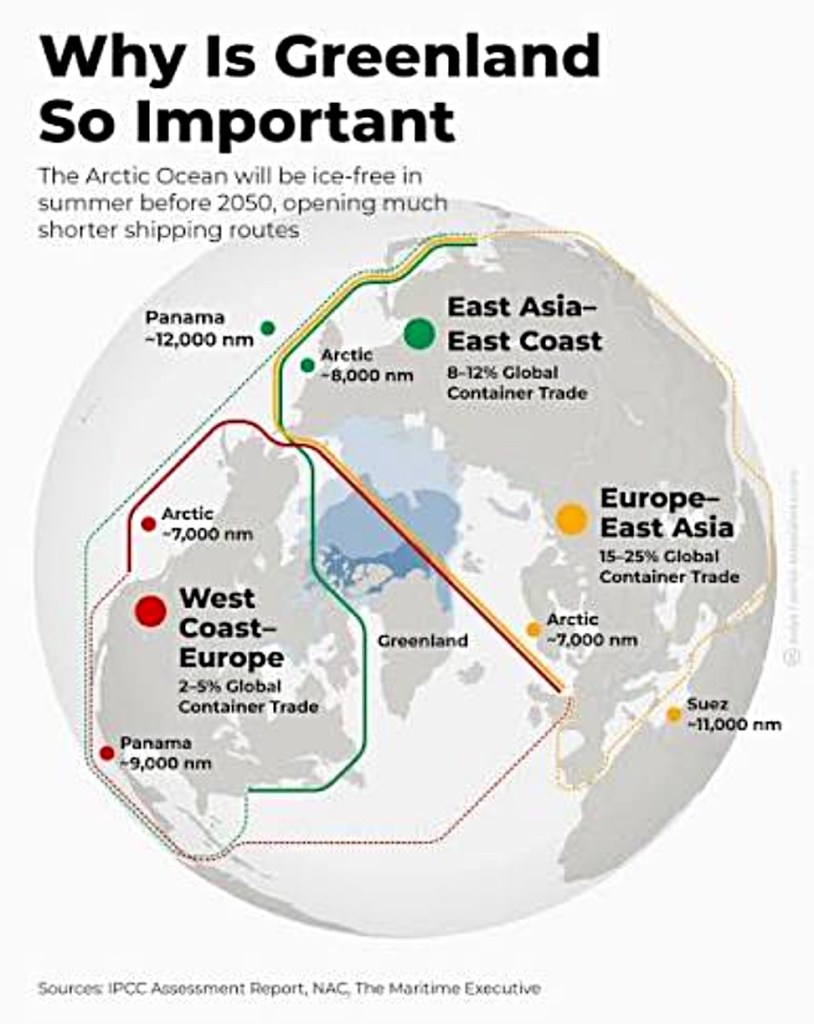

A United States move against Greenland under a Trump administration would demand a response designed not to soothe Washington, but to constrain it. The tools exist. What has been lacking is the willingness to use them against an ally that behaves as though alliance membership confers impunity.

The first step would be political isolation, executed collectively and without ambiguity.

NATO members, alongside key non NATO partners, would need to suspend routine diplomatic engagement with the US administration itself. Not the American state. Not American civil society. The administration. This distinction matters. Ambassadors would be recalled for consultations. High level bilateral visits would cease. Joint communiqués would be frozen. Washington would find itself formally present in institutions, but substantively sidelined.

This is not symbolic. Modern power depends on access, legitimacy, and agenda setting. Denying those channels turns raw power into blunt force, costly and inefficient.

The second step would be economic containment, targeted and coordinated.

The mid twentieth century model of blanket sanctions is outdated. Today’s leverage lies in regulatory power, market access, and standards. European states, Canada, and aligned partners would move to restrict US firms closely tied to the administration’s political and financial ecosystem. Defense procurement would be restructured. Technology partnerships would be paused. Financial scrutiny would intensify under existing anti corruption and transparency frameworks.

None of this would require new treaties. It would require resolve.

The message would be clear. Aggression inside the alliance triggers costs that cannot be offset by military dominance alone.

Third, alliance structures themselves would need to adapt in real time.

NATO decision making, already consensus based, would be deliberately narrowed. US participation in strategic planning, intelligence fusion, and Arctic coordination would be curtailed on the grounds of conflict of interest. Parallel European led and transatlantic minus one mechanisms would emerge rapidly, not as an ideological project, but as operational necessity.

This would mark a shift from alliance dependence to alliance resilience.

The fourth pillar would be legal and normative escalation.

Denmark, backed by partners, would pursue coordinated legal action across international forums. Not in the expectation that courts alone would reverse an annexation, but to delegitimize it relentlessly. Every ruling, every advisory opinion, every formal objection would build a cumulative case. The objective would not be immediate reversal, but long term unsustainability.

Occupation without recognition is expensive. Annexation without legitimacy corrodes from within.

Finally, and most critically, allies would need to speak directly to the American public over the head of the administration.

This is not interference. It is alliance preservation. The distinction between a government and a people becomes essential when one diverges sharply from shared norms. Clear, consistent messaging would emphasize that cooperation remains available the moment aggression ceases. The door would not be closed. It would be firmly guarded.

The aim of this strategy is not punishment for its own sake. It is containment without war.

The twentieth century taught the cost of appeasing expansionist behavior. The twenty first century demands something more precise. Not tanks crossing borders, but access withdrawn. Not ultimatums, but coordinated exclusion. Not moral outrage alone, but structural consequences.

A United States that chooses coercion over cooperation cannot be met with nostalgia for past alliances. It must be met with a clear boundary. Power inside a system does not grant license to dismantle it.

The survival of NATO, and of the broader rules based order it claims to defend, would depend on allies finally acting as though that principle applies to everyone. Including the strongest member of the room.